ART

Photography of Frida Kahlo with Picasso Earrings. Photo: Nickolas Muray, American, 1892-1965. Nickolas Muray Photo Archive © Nickolas Muray Photo Archive

Artcentron celebrates the famous Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, who had a difficult life but excelled as an artist, fashion icon, and feminist.

BY KAZEEM ADELEKE

In modern art history, the story of Frida Kahlo stands out as something of a legend. Fondly called Frida, her original name was Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón. Born on July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, Mexico, the celebrated artist died on July 13, 1954. She was 47 years old. Although Frida has been dead for over six decades, her popularity continues to grow in the art community. Many books have been written about her, including a recent one titled Forever Frida by Kathy Cano-Murillo.

Frida Kahlo’s works have also been the subject of many exhibitions across the globe. The most recent was Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving at the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York. The massive show followed another show at the 2015 blockbuster exhibition at the New York Botanical Garden. Titled Frida Kahlo: Art, Garden, Life, the show was the first to examine Frida’s appreciation for the beauty and variety of the natural world. In 2002, Frida, a movie about Frida Kahlo’s life was released to great acclaim. It won several awards, including the Academy Award for Best Music Score.

Frida Kahlo: A Difficult Childhood

Frida had a difficult childhood marked by health problems and tragedies. At the young six, she suffered a bout of polio, a condition that left her with a slight limp because one of her legs was longer than the other. Her peers bullied and tormented her because of her physical disability, and the diseases that isolated her for long periods. They called her “peg leg.” Although Frida is well-known today across the globe for her art, art was not her first choice. As a young girl, she was more interested in science, and in 1922, she entered the National Preparatory School in Mexico City with an interest in eventually studying medicine. With a clear focus, Frida excelled in medical school.

While at National Preparatory School, she met and fell madly in love with Alejandro Gomez Arias. The two were happy and looking forward to the future together. That was until one arduous September afternoon.

Bus Accident: Frida Kahlo and Alejandro

In 1925, Frida was on her way about town with her boyfriend Alejandro Gomez Arias when the bus they were traveling in collided with a trolley. A new book Forever Frida by Kathy Cano- Murillo details the impact of that accident: “Frida was thrown from the vehicle, and a steel handrail impaled her through one side of her pelvis and out from between her legs. Her clothes ripped away and she lay naked in the street, bleeding, and covered only by gold powder that had spilled from the hands of another passenger. Before Alejandro had the chance to act, a man anchored his knee to Frida’s body and ripped out the pole. Alejandro and Frida screamed so loud that he couldn’t even hear the ambulance.”

Frida sustained massive injuries that left her bedridden for months. In addition to sustaining three breaks to the lumbar region of her spinal column, she also suffered “a broken collarbone, two broken ribs, eleven fractures in her right leg, a crushed right foot, and three breaks to her pelvis.”

Frida went through many surgeries that left her in a lot of pain. The fading love between her and Alejandro added more layers to her pain. Bedridden, lonely, and depressed, Frida turned to art for respite. She taught herself to paint and read frequently, studying the art of the Old Masters. Although Frida took some drawing classes when she was younger, it was during her recovery from the bus accident that she boldly embraced art.

Guillermo Kahlo, Frida Kahlo, and Photography

Guillermo Kahlo, Frida’s father, was a major source of influence on his daughter. One of the top photographers in Mexico at that time, Guillermo made a name for himself taking photographs of churches and landmarks. Monuments, streets, factories, and friends. Frida frequently assisted her father in his work and the studio. Frida’s father had epilepsy and Frida ensured that his equipment was safe during episodes. Through this, she gains a keen eye for details.

Frida adored and worshiped her father for his intellectual pursuits of photography, reading, painting, and liberal views. Her love and devotion to her father are evident in a portrait of him she painted in later years. The portrait shows her father with his camera. On the painting, she wrote:

“I painted my father Wilhelm Kahlo, of Hungarian-German origin, artist-photographer was his profession, of generous character, intelligent and refined; courageous because he suffered from epilepsy for 60 years but not once did he stop working or fighting against Hitler. With adoration from his daughter Frida Kahlo”

Frida Meets Diego

The relationship between Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo began as a joke. While Diego was working on his first major mural project, Creation, at the Bolívar Auditorium of the National Preparatory School in Mexico City in 1922, Frida would sneak into the auditorium to prank him. Frida was one of the thirty-five female students at the prestigious institution. In the book, My Art, My Life: An Autobiography, Diego recalls the enormity of Frida’s pranks. “While painting, I suddenly heard, from behind one of the colonial pillars in the spacious room, the voice of an unseen girl,” he recalled. Frida was playful and exuberant. In one instance, she teased Diego, calling out, “On guard, Diego, Nahui is coming!” Nahui was a talented woman painter posing for one of the auditorium figures.

Frida Kahlo tormented Diego with her pranks and youthful exuberance for many weeks. One night, while working on his mural, Diego heard a loud commotion coming from a group of students pushing against the auditorium door. Then a teenager, Frida bursts into the hall, mischief written all over her face. “All at once the door flew open and a girl who seemed to be no more than ten or twelve was propelled inside,” recalled Diego in his biography.

Like many other students in the school, Frida Kahlo was wearing her school uniform. However, what differentiated her from others was her attitude. Diego described her thus: “She had unusual dignity and self-assurance, and there was a strange fire in her eyes. Her beauty was that of a child, yet her breasts were well developed.”

In the auditorium, Frida Kahlo looked at Diego Rivera who was on the scaffolding working straight in the eyes, and asked, “Would it cause you any annoyance if I watched you at work?” Diego replied, “No, young lady, I’d be charmed”.

For several hours, Frida attentively watched Diego as he worked on the mural. However, as time wore on, Diego Rivera’s wife, Guadalupe “Lupe” Marín, who was working below, could not take it anymore. She found Frida’s presence threatening and could not take it anymore. Her blood boiled as jealousy rose. Unable to control her emotions, she rained insults on Frida who ignored her. Frida’s silence sent Lupe’s blood on fire, and she confronted her. Diego describes the encounter thus: “Hands on hips, Lupe walked toward the girl and confronted her belligerently. The girl merely stiffened and returned Lupe’s stare without a word.”

Frida Kahlo was unperturbed by Lupe’s display of aggression. Instead of flinching, she engaged Lupe’s gaze for gaze. Lupe was amazed by Frida’s boldness. Soon aggression became admiration. “Look at that girl! Small as she is, she does not fear a tall, strong woman like me. I really like her,” Diego recalls Lupe saying.

Diego and Frida did not cross paths again until years later. Again, it was because of Frida Kahlo’s exuberance. One day, Diego was busy working on one of the uppermost frescoes at the Ministry of Education building when he heard a girl yelling out his name. “Diego, please come down from there! I have something important to discuss with you!” It was Frida Kahlo.

When Diego looked down, he saw a beautiful woman about eighteen years old. She has long hair and thick eyebrows that meet above her nose. Little did Diego know that it was Frida; the little girl that tormented him with her pranks many years ago. The pupa has become a butterfly, and Frida is now a woman.

Frida wanted Diego’s professional view of her paintings. In her collection were three portrait paintings. Diego was impressed not just by Frida’s unique skills but also by her style and honesty. “It was obvious to me that this girl was an authentic artist,” Diego recalls in his book. Frida, who already knew of Diego’s reputation with women, would not have any of his sweet nothings. Her response was pointed: “I have not come to you looking for compliments. I want the criticism of a serious man,” she said scolding him in the harshest defensive tone.

Frida was persistent, and Diego’s response was clear: “In my opinion, no matter how difficult it is for you, you must continue to paint,” he said. Not satisfied, Frieda invited Diego to her studio to see more work. When Frida told Diego her name and address, a bell went off. Diego realized that Frida was the girl who pulled all the pranks on him and stood her ground when confronted by his wife.

Frida and Diego: The First Kiss

Diego’s visit to Frida’s studio marked the beginning of a turbulent relationship. Frida and Diego kissed two days after that visit. Frida was 18 and Diego 40, but that did not matter to the new lovers. Soon after, they decided to get married. Frida’s mother was against the union, but her father supported it because Diego was a successful artist, a notable figure in the Mexican Communist Party, and had the financial means to support Frida. On August 21, 1929, Frida and Diego got married in a civil ceremony by the Mayor of Coyoacán, one of Mexico City’s sixteen boroughs. Diego was 42 and Frida 22. Struck by the age difference, the Mayor proclaimed the merger “a historical event.”

Frida and Diego: A Turbulent Marriage

The marriage between Frida and Diego was a roller coaster. Although they were together until Frieda died in 1954, the marriage was marked by deceit, deception, betrayal, and dishonesty.

Growing up, Frida was a free spirit with an open mind. She was vivacious and could not understand nor relate to the traditionalist view of women personified by her Catholic mother, which emphasized that women should be subservient to their husbands and be homekeepers. Not surprisingly, Frida developed an animosity toward the Catholic Church that propagated such an idea. For her, such tradition amounted to the subjugation of women and she did not want any part of it. Frida was a modern woman who loved fashion and freedom of expression. Sadly, all that spirit disappeared after marrying Diego.

Frida began to change soon after her marriage to Diego. First, to change was her personality. She began to wear the traditional Tehuana dress that comprised a flowered headdress, a loose blouse, a piece of gold jewelry, and a long, ruffled skirt. Wherever she went, she flaunts her beauty enhanced by her new fashion sensibility. This fashion style and sensibility soon became her hallmark.

Frida’s painting style also changed. Besides a new interest in fashion and Mexican Folk Art, the figures in her new paintings became flatter and more abstract, a total contrast to her earlier paintings where the figures are rounded. An important example of the change is evident in Frieda and Diego Rivera, a 1931 painting. The painting depicts Frida and Diego holding hands. On the right side of the painting is Diego wearing a black suit, blue shirt, brown belt, and shoes. In his right hand is a palette and some brushes, the objects of his profession. Diego looks dignified and accomplished. Standing beside the tall Diego is the petite and demure Frida dressed in her signature attire.

Frieda and Diego Rivera is very revealing as it provides an insight into what was going on in the marriage, especially the role of Frida. The first noticeable indicator is that while Diego looks modern in his suit, Frida looks traditional in her attire. The painting also privileges Diego over Frida in terms of accomplishment. While Diego appeared modern and successful standing close to the foreground of the painting, Frieda would have disappeared into the background but for the red scarf around her shoulder. The painting seems to suggest that Frida assumed the role of the traditional Mexican wife soon after getting married, an idea she abhorred.

Frida and Diego in the United States

Frieda and Diego Rivera was painted when the couple was traveling across the United States from 1930 to 1933. Diego had received several commissions to create murals in the United States, and Frida went with him. The trip presented some unexpected challenges for Frida. First, she had to endure several difficult pregnancies that ended prematurely. One such miscarriage happened in Detroit where Diego was working on a mural at the Detroit Institute of Art. The doctors tried but could not save the baby and an abortion was performed. While dealing with the adversities of her miscarriages and abortion, Frida got the news that her mother was dead during childbirth.

Frida was traumatized by the events of this period and they translated into her harrowing works. In Henry Ford Hospital (1932), for instance, Frida depicts her small, helpless body hemorrhaging on a white enormous hospital bed after an abortion was performed. Her stomach was swollen, and she looked gruesomely emaciated. Tears pouring from her eyes show her pain. On the horizon is a barren landscape of Detroit where Diego was working.

The painting includes six important elements pointing to Frida’s deep depression, desires, and state of mind. Attached to her hand by red ribbons referencing umbilical cords, are several symbolic elements of desires and pain. Floating above her bed on the right side is a snail, a male fetus, and a pink orthopedic cast of the pelvic zone. Below, on the left side of the bed is a machine, an orchid, and a pelvic bone. Henry Ford Hospital is a painting of fear, pain, love, longing, and insurmountable trauma.

In 1932, Frida continued to illuminate the challenges of childbirth, miscarriages, and abortion in her paintings. In My Birth (1932), Frida painted a woman giving birth. The painting captures the birth of a child at the exact moment the baby is emerging from the woman’s womb. There is a puddle of blood on the bed under the woman’s body. A sheet covers the mother’s face as if dead. Above the birth bed, is a picture of the weeping “Virgin of Sorrows” helplessly watching the gory episode.

Although traditionally considered taboo to paint such topics as a woman giving birth, the painting tells stories about Frida’s life and other women in their struggles with giving birth. Frida explained in her journal that the painting depicts a rebirth of herself. However, there are references in the frightening large painting that point to Frida’s struggle with having children. While the sheet covering the woman’s face references the death of Frida’s mother, the woman giving birth points to Frida’s recent miscarriage and abortion. The painting is in the collection of the Popstar Madonna.

In 1933, Frida and Diego returned to Mexico. They immediately settled in a newly constructed house made of separate individual spaces connected by a bridge. The available space was an opportunity for the couple to entertain friends and host parties. Political activists and many artists, including Leon Trotsky and André Breton, a leading Surrealist who championed Kahlo’s work met at the house.

First Solo Exhibition in New York

Frida’s first exhibition was held at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1938. It was a huge success. In the introduction to the exhibition, André Breton described Frida as a self-taught Surrealist. The exhibition opened new doors for Frida and in 1939; she traveled to Paris to show her new work. In Paris, Frida got attention from collectors, galleries, museums, and artists. She met more members of the surrealists including Marcel Duchamp, the only member she reported respected. During this visit, The Louvre acquired one of Frida’s works, The Frame (c.1938). The acquisition made her the first 20th-century Mexican artist to be included in the museum’s collection.

Divorce: Infidelity and Betrayals

By the mid-1930s, the marriage between Frida and Diego was on the rocks. Shifty-eyed Diego could not focus on beautiful Frida and soon maneuvered to her younger sister Christina. Frida was crushed by her husband’s illicit affair with her younger sister. She documented her pain in the 1937 painting Memory, the Heart.

The relationship between Diego and Frida’s sister was just one of the extramarital affairs Diego had. Throughout their marriage, Diego was engaged in many extramarital affairs. However, Diego was not alone in his infidelity. Frida also had extramarital relationships with several men and women, the most notable were the French singer, dancer, and actress Josephine Baker and Russian Marxist theorist Leon Trotsky.

Frida and Diego divorced in 1939, 10 years after their marriage. Distressing as the dissolution of the marriage was, it enhanced Frida’s creativity. She created some of her seminal works that year. One of the notable works from this era was The Two Fridas 1939. Measuring 5.69 × 5.68 feet, this unusually large canvas allows an insight into Frida’s two personalities. The painting depicts two Fridas holding hands. The hearts of the two Fridas are visible.

On the left side of the painting is Frida in the traditional Tehuana attire. The blue blouse with orange stripes matches the golden brown skirt. In her hand is an Olmeca figurine representing Diego. The heart of the indigenous Frida looks perfect and well cared for. From it, an artery links to the Diego figurine she holds in her left hand. Another artery from that heart connects to the Frida on the right of the painting wearing a European-style wedding dress. The anatomy of the heart on the independently dressed Frida is exposed. From the torn heart comes an artery that goes down the right hand. The artery is cut off with a surgical pincer and blood drips, staining the beautiful white dress. It is a hallowed heart. Behind the portraits is a stormy sky with agitated clouds.

In her diary, Frida explained that The Two Fridas represents memories of her mother but later admitted that it expressed desperation and loneliness with the separation from Diego. Like many of Frida’s works, the painting is subject to multiple interpretations. However, the one that continues to hold sway among art historians is that it addresses the toxic relationship between Frida and Diego. While the Frida with the traditional attar epitomized Diego’s desires, the Frida in the independent dress was an antithesis of his perception of women and the place of a wife. The Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes (National Institute of Fine Art) in Mexico City acquired the painting in 1947. It paid a little over $1000 for it, making it the highest price Frida got for her painting during her lifetime. A reproduction of the painting is on display in Frida Kahlo Museum in Coyoacan, Mexico.

The Two Fridas is just one of the paintings Frida used to express the misery of her divorce from Diego. Self-Portrait With Cropped Hair (1940) is another. In the painting, Frida depicts herself wearing an oversized suit similar to the one Diego wore. She sits on a cane chair in a room. In her hand is a pair of scissors used in cutting her hair that lay on the floor around her. Frida’s haircutting ritual was not only an expression of grief but also a castigation of Diego who loved her long black hair.

Even as Frida was dealing with the affairs of the heart, she contracted gangrene, and her right leg was amputated at the knee. It was like adding salt to injury. She became even more depressed. Frida equated her relationship with Diego to an accident. She wrote in her diary “There have been two great accidents in my life. One was the trolley, and the other was Diego. Diego was by far the worst.”

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: Back Together Again

The divorce between Frida and Diego lasted for only one year. In 1940, the couple reconciled and moved into Frida’s childhood home, La Casa Azul (“The Blue House”), in Coyoacán. Even as Frida was making progress in her artistic career, poor health held her back. In 1943, she was appointed a professor of painting at La Esmeralda, the Education Ministry’s School of Art, but failing health made it impossible to achieve her potential.

To deal with pain and depression, Frida turned to the bottle and drugs for relief. Despite all the turbulence in her life, Frida continued painting. In the 1940s, she painted many self-portraits. In these portraits, she projected the way she wanted to be seen, appearing in various hairstyles, clothing, and iconography. She looked impressive and presented a steadfast gaze that became her hallmark.

Between the early 1940s and 50s, Frida underwent several surgeries with often prolonged stays in the hospital. Towards the end of her life, Frida was dealing with many health issues. She had difficulty working and required some assistance. In 1951, she appeared in Self-Portrait with Portrait of Dr. Farill. In the painting, Frida is in a wheelchair. When her first solo exhibition opened in Mexico in 1953, she was too ill to attend and was taken to the venue lying on a bed. She died in La Casa Azul in 1954, the official cause documented as a pulmonary embolism.

Self-Portraits: Frida Kahlo Paintings

Almost half of Frida Kahlo’s paintings are self-portraits. These self-portraits actualize events in her life. From love to pain, tragedies, and betrayal, the self-portraits tell many stories. One such portrait is The Broken Column. Painted in 1944, Frida depicts herself almost nude. A split that looks like an earthquake fissure runs from her neck through her torso. Within the split is a broken decorative column that has taken the place of the spine. It runs from her chin to her loin. Frida’s body is held together with a white fitted surgical brace, which exposes her breasts. Nails are sticking out all over her body, including her face which is filled with tears. Around her waist, covering the lower part of her body is a white cloth. Behind her is a turbulent landscape with deep dark rifts.

The Broken Column is a jarring and touching subject filled with anger, frustration, and anguish. Nonetheless, boldness shines through the striking composition. Frida appears strong and unfazed by her tribulations. Her penetrating gaze, accentuated by her converging eyebrows and black hair, forces the viewer to return her gaze. There is a religious, perhaps, spiritual element, inherent in the painting. The cloth around her waist, the penetrating nails, the exposed body, and the column running through her body have references in religious paintings.

Self Portrait in a Velvet Dress is one of the earliest self-portraits by Frida. Painted in 1926 in the style of 19th-century Mexican portrait painters, it shows Frida wearing a wine-red velvet dress. She looks radiant and princess-like. The painting was created at the height of the conflict with Alejandro, her lover. Alejandro thought Frida was too liberal and wanted nothing to do with her. Frida, who was head over heels in love with him, created the painting as a peace offering aimed at winning back Alejandro’s heart. In addition to the painting, Frida also expressed her love through letters. In one of her letters, she wrote, “Within a few days, the portrait will be in your house. Forgive me for sending it without a frame. I implore you to put it in a low place where you can see it as if you were looking at me.”

Self Portrait in a Velvet Dress worked and soon Frida and Alejandro were back together again. Then, something bad happened. In March 1927, Alejandro’s parents sent him to Europe to keep him away from Frida. All efforts to get him back even after he returned to Mexico failed. Neither Self Portrait in a Velvet Dress nor love letters could reconnect their broken affection.

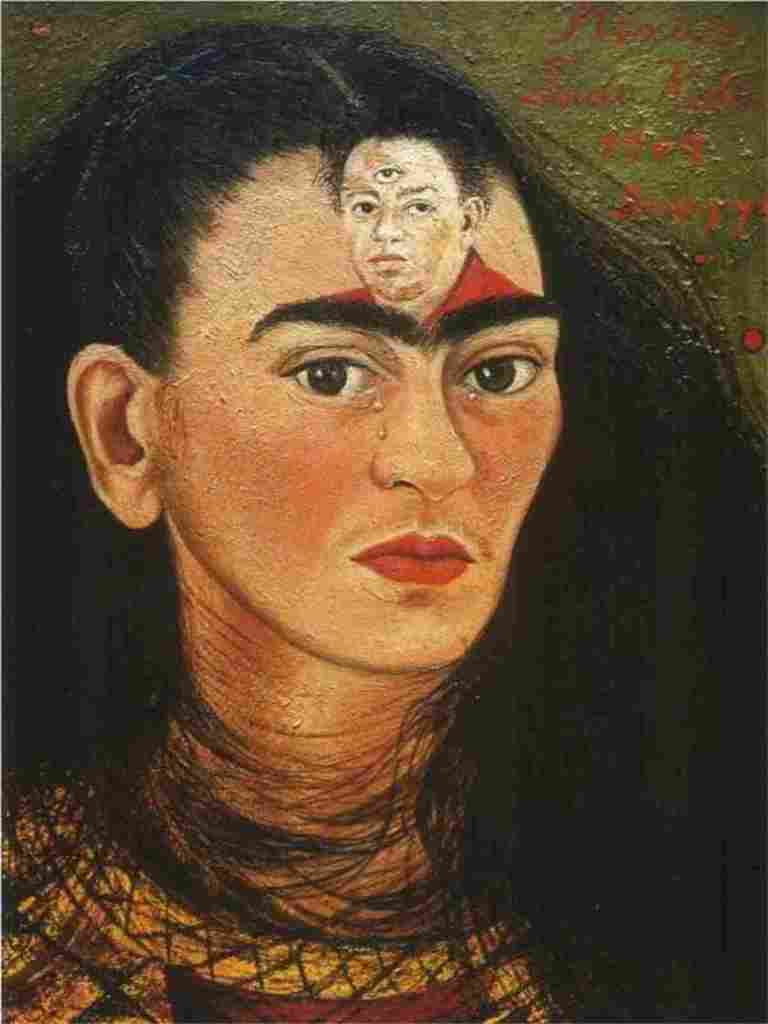

Fleeting love is at the core of Diego and I. Painted in 1949, the self-portrait is a lamentation for her cheating lover and husband. Around 1949, Frida found out that Diego was having an affair with the beautiful film star Maria Felix who was Frida’s friend. So serious was the relationship that Diego almost divorced Frida. Diego and I is a response to the dishonest husband.

Diego and I has the image of Frida with tears dripping from her glistering eyes. Her hair is loose and hangs around her neck as if strangling her. Inscribed on her forehead is an image of Diego wearing a red shirt. On Diego’s forehead is a third eye, the all-seeing eye. The painting expresses Frida’s anguish of betrayal by her lover. Nevertheless, behind that agony is a beautiful woman. Frida made herself even more beautiful in this painting. Her well-nurtured eyebrows, red luscious lips, and beautiful flesh tones leave no doubt that this is a beautiful woman. Perhaps, Frida is presenting herself as more beautiful than the other woman

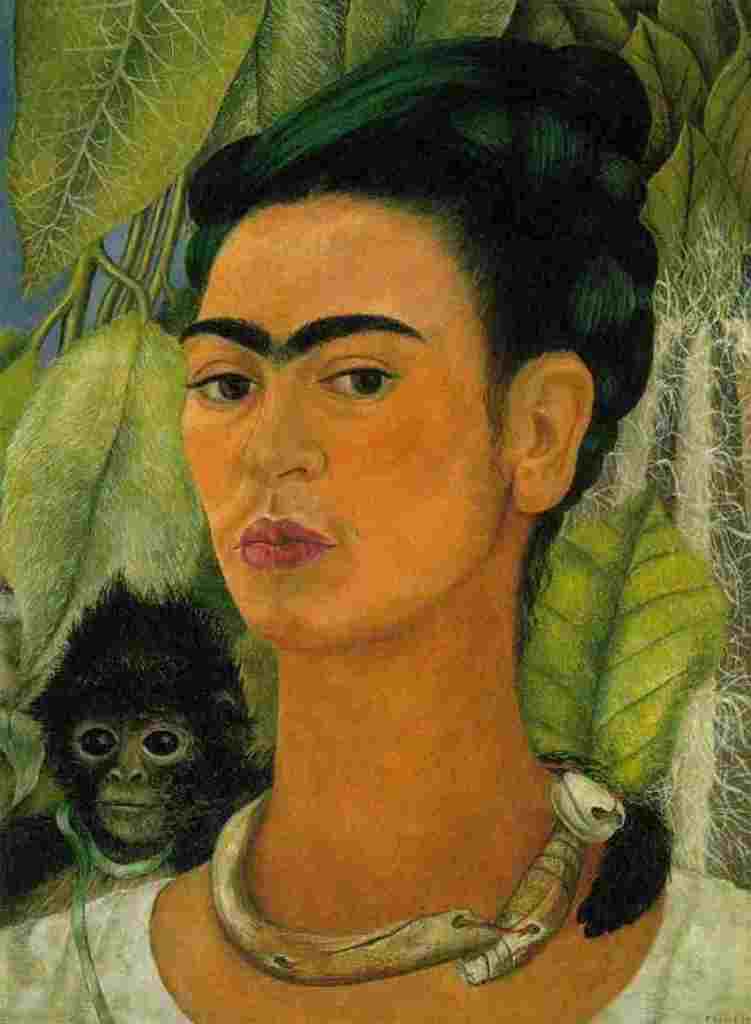

Frida appeared with animals in some of her self-portraits. One of them is Self Portrait with a Monkey. Painted in 1938, the painting has a portrait of Frida. In the background is a big curtain of leaves. Hiding among the leaves and resting on Frida’s shoulder is a black monkey with two black eyes. The monkey has one hand over Frida’s shoulder as if comforting her or showing her affection. Although the monkey is a symbol of lust in Mexican mythology, Frida presents the monkey just as a loving pet. Anson Conger Goodyear, former president of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, commissioned the painting after seeing Frida’s work in her first show in New York.

Some other important self-portraits by the artist include Self-portrait – Time Flies (1929), Portrait of a Woman in White (1930), and Self-Portrait Dedicated to Leon Trotsky (1937) among many others. Self Portrait – Time Flies was on auction at Sotheby’s in New York for five million dollars in 1920. The auction record makes Kahlo the highest-selling Latin American artist in history.

Was Frida Kahlo a Surrealist?

This question has been the subject of discussion for decades among art historians. The question was predicated on Frida’s association with the surrealists. In 1940, Frida Kahlo took part in the International Exhibition of Surrealism at the Galeria de Arte, Mexicano. The art exhibition included two of her works: The Two Fridas and The Wounded Table (1940). Furthermore, André Breton, a Surrealist, considered Kahlo a surrealist. However, while the surrealists claimed Frida as one of their own, she rejected them outright, noting, “They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”

Frida Kahlo: Life After Death

Frida Kahlo died on July 13, 1954. After her death, La Casa Azul was redesigned as a museum dedicated to her life. Frida was born and grew up in La Casa Azul, whose cobalt walls gave way to the nickname of the Blue House. In 1958, the Frida Kahlo Museum opened to the public, a year after Diego’s death. On display in the museum are Frida’s personal belongings arranged as if she still lived there. The museum is the most popular museum in the Coyoacan neighborhood and among the most visited in Mexico City.

The Diary of Frida Kahlo, covering the years 1944–54 and The Letters of Frida Kahlo were published in 1995. They illuminate events in her life. Although Frida achieved artistic success during her lifetime, her reputation grew even more after her death. Starting from the 1970s, she began to garner a reputation that skyrocketed years after. By the 21st century, she had achieved a pop icon status and what the critics call “Fridamania”.

The story of her life became something of a legend. From the crippling injury from the bus accident to her turbulent marriage to Diego, the sensational love affairs, and the heavy drinking and drug use, many books have been celebrating Frida Kahlo’s life. Her works have been at the center of many exhibitions, and her face is on tee shirts and many other everyday things.