ART

Critics once hated Picasso’s late works. See why a new generation of artists found inspiration in his final paintings at Moderna Museet.

BY KAZEEM ADELEKE, ARTCENTRON

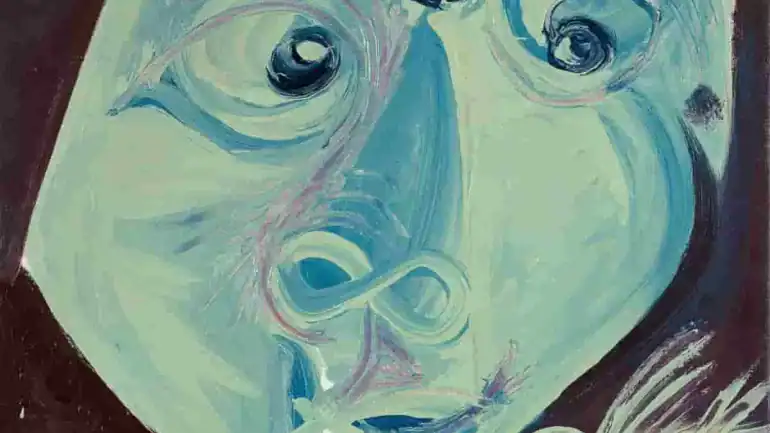

The final chapter of Pablo Picasso’s life was not a quiet fade into the background. Instead, it was a period of frantic, raw, and unapologetic creation. The current exhibition at Moderna Museet Stockholm, titled “Late Picasso,” invites the public to witness the intense energy of an artist in his eighties who refused to stop evolving.

The Transformation of Picasso’s Late Works

Between 1963 and 1973, Picasso retreated to his studio in Mougins. While the art world moved toward the cold precision of minimalism, Picasso doubled down on the human form. Picasso’s late works represent a shift from the calculated genius of his youth to a more spontaneous, gestural style. He painted with an urgency that ignored traditional “polished” finishes, often completing multiple canvases in a single day.

Why Moderna Museet Stockholm is Revisiting the Legend

This exhibition marks the first major showcase of the artist at Moderna Museet Stockholm in over three decades. Curated by Jo Widoff, the collection features eighty pieces, including fifty paintings and thirty works on paper. These items highlight a “deliberate refusal to be conclusive.” For Picasso, the canvas was no longer a place for answers but a threshold where life and art collided.

From Critical Rejection to Modern Influence

It is hard to imagine now, but critics once dismissed these pieces as the “chaotic” output of a declining mind. However, the narrative shifted dramatically in the 1980s. A new generation of neo-expressionist painters looked at the “untamed vitality” of Picasso’s late works and saw a blueprint for the future.

The 1981 exhibition “A New Spirit in Painting” was a turning point. It placed Picasso’s final canvases alongside modern icons like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Georg Baselitz. This solidified his status not just as a historical figure, but as a prophetic force that predicted the expressive freedom of the late 20th century.

Picasso’s Late Works: A Complex Legacy in the Modern Era

Today, we view Picasso through a more nuanced lens. While his technical mastery remains undisputed, modern scholars at institutions like Moderna Museet Stockholm now explore his work through feminist and postcolonial critiques. He is no longer an “untouchable icon” but a complex figure who helps us understand the contradictions of the modern world.

- Featured Image: Pablo Picasso, Tête à l’oiseau/Head with Bird, Mougins, May 8, 1971 (II). Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso, Madrid. © Succession Picasso/Bildupphovsrätt 2025. Photo: Eric Baudouin © FABA