ART AUCTION

Behind Gustav Klimt Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer lies a tale of betrayal, survival, and artistic genius. See why it could set a new auction record.

BY KAZEEM ADELEKE, ARTCENTRON

Gustav Klimt’s Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer (1914–1916), a masterwork of historical importance and artistic significance, is the highlight of this autumn’s auction season. The painting, an unfathomable canvas expected to fetch up to $150 million, comes from the private collection of the late cosmetics baron Leonard Lauder. It will inaugurate Sotheby’s new flagship at the Breuer Building with a marquee evening auction on November 18.

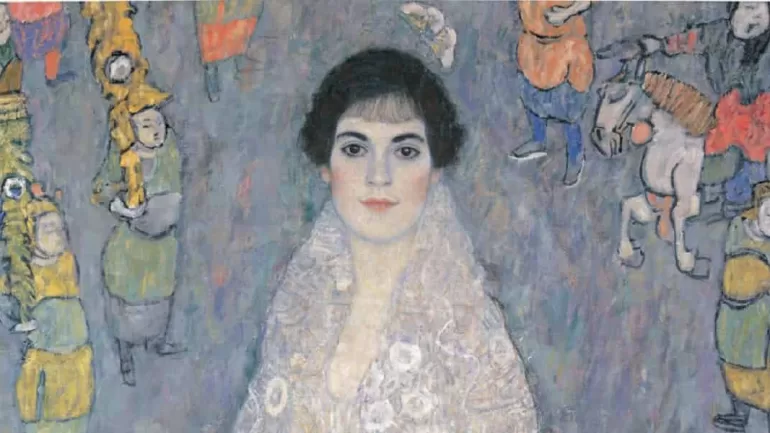

This stunning artwork portrays a statuesque young woman in a translucent white gown and cerulean-patterned mantle. Behind her, tiny Chinese figures on an ornamental tapestry and a rug of blush and tangerine motifs create an eccentric backdrop. The painting’s history is as complex as its visual language. It was previously on anonymous loan to the National Gallery of Canada and, earlier, to the Neue Galerie, an institution co-founded by Lauder’s brother, Ronald, where it was part of a lauded 2016 exhibition that reunited it with her mother’s portrait.

Should the painting meet its high estimate, this Gustav Klimt portrait of Elisabeth Lederer could shatter the artist’s standing auction record of £85.3 million ($108.4 million), set in 2023 for Dame mit Fächer. While that sale crowned it Europe’s priciest artwork sold at auction, the private market for Klimt has surpassed that sum, as demonstrated by Oprah Winfrey’s 2016 resale of Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II for $150 million. Yet, its price barely scratches the surface of the Gustav Klimt Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer’s mystique. Even without the gold-leaf opulence of The Kiss or Adele Bloch-Bauer I, it remains a visual sonata and a historical cipher. Below are three enigmatic revelations buried within its provenance.

A Canvas Stitched Through Generations

Commissioned by August and Serena Lederer, the portrait immortalized their daughter, Elisabeth, who was only 20 during its inception. Serena, a muse to architect Josef Hoffmann, had also sat for Klimt in 1899. That first portrait, now at the Metropolitan Museum, bears an uncanny resemblance to Elisabeth: twin-like delicacy and eyes that echo across bloodlines. While her mother’s piece was lauded as Symphony in White, Elisabeth’s is enveloped in interesting hues and cross-cultural textures. This matriarchal image cemented Klimt’s bond with the family, which endured until his death. In a masterstroke of foresight, Serena purchased the entirety of his remaining studio contents, amassing the most robust Klimt collection in existence, including the monumental Beethoven Frieze.

Klimt’s dependence on their patronage was existential. In a letter seeking payment for a portrait of Serena’s mother, he wrote, “I await it as the damned await absolution.” In a bittersweet reunion, both the portraits of Elisabeth and Serena reappeared at the Neue Galerie in 2016. Sadly, the portrait of Charlotte, Serena’s mother, remains lost. In 1940, Nazi forces confiscated the Lederer trove, relocating much of it to Schloss Immendorf. As the war closed in, the retreating Wehrmacht set the castle ablaze, reducing up to ten of Klimt’s masterworks to scorched ash.

Gustav Klimt Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer

Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Baroness Elisabeth Bachofen-Echt (c. 1914–1916). Oil on canvas, 180 x 126 cm (70.8 x 49.6 in). Private collection. PD–PDUSA

A Lie That Preserved a Life

The Lederers, affluent Jewish industrialists, were among Austria’s elite. When the Nazi regime annexed Austria in 1938, Serena fled to Hungary. Elisabeth, who had divorced her Protestant nobleman husband, remained in Vienna, vulnerable and exposed. In a move both desperate and strategic, Elisabeth asserted a stunning claim: that she was Klimt’s biological daughter. The artist, famously unattached and father of at least 14 children, became her imagined lifeline. With Serena’s written affirmation, she wove a tale of clandestine conception, capitalizing on her art education to bolster the illusion.

Historians later unraveled the fiction, but the Nazi Reich Genealogical Office accepted it. By their ledger, she was “half-Aryan.” The deception shielded her from deportation. Though she would not outlive the war, it spared her the brutal machinery of the Holocaust. In 1948, after her death, both the Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer and her mother’s painting surfaced at a Vienna auction. Her brother, Erich, intervened to reclaim them through restitution efforts.

Imperial Ghosts Weave Through the Fabric

While Serena’s portrait conjured Whistler’s ethereal Western motifs, Elisabeth’s composition reveals a matured Klimt. The figure stands serene, yet the scene hums with symbolism. The patterned robe she wears isn’t mere exoticism—it whispers dynastic intent. Years of meticulous brushwork culminated in this canvas, and it was Serena, not Klimt, who finally declared the painting complete—rumor has it she plucked it from his easel mid-process.

Gustav Klimt Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer Reveals Secrets

Unlike Klimt’s shimmering gold mosaics, this Gustav Klimt portrait of Elisabeth Lederer is rendered in austere chromatics—icy blues, gentle grays, and a robe that seems to flatten like a decorative screen. A closer look reveals a secret. Kirsten Appleyard, curatorial assistant at Canada’s National Gallery, revealed, “Hidden within her robe are two pale blue dragons rising from crested waves.” These ancient symbols of emperorship mark the garment as an imperial Chinese cloak. Though Klimt flirted with Asian designs in other works, this is his sole canvas to embed such sovereign iconography. It’s a visual benediction—a gesture of reverence to the Lederers, a family who underwrote the evolution of his genius.

A century later, the Portrait of Elisabeth Lederer remains not merely an artwork but a relic of patronage, survival, and the cryptic dialogue between painter and muse. The Gustav Klimt portrait of Elisabeth Lederer endures as more than canvas and paint; she is myth, memory, and the embodiment of a forever-eclipsed era.