ART REVIEW

Fabric of a Nation: Quilt Stories of Protest, Memory, and Identity

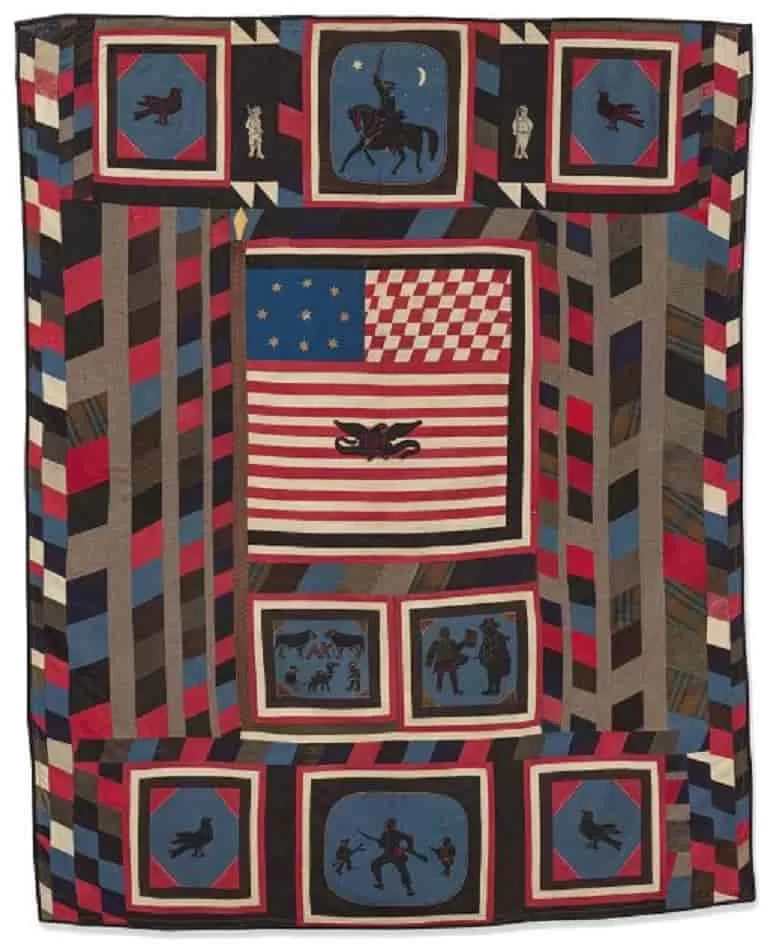

posted by ARTCENTRONInstallation view of Virginia Jacobs’ Krabow Kabuki Waltz on display at the Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories exhibition. Gift of the artist. Reproduced with permission. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories at the First Art Museum, Nashville, is a powerful exploration of how quilts express protest, preserve memory, and shape American identity through powerful visual storytelling.

BY KAZEEM ADELEKE, ARTCENTRON

NASHVILLE, TN – In a time of national self-examination, the First Art Museum is hosting Fabric of a Nation: American Quilt Stories, a remarkable traveling exhibition that traces over 300 years of American cultural, artistic, and political evolution. Originating from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), the show features nearly 50 quilts and coverlets. It explores quilting as both a utilitarian craft and a narrative medium. The works, produced by a diverse array of makers—often from historically marginalized communities—illuminate themes central to the American experience, including identity, resilience, justice, and belonging.

Quilting, long valued for its domestic and communal roots, emerges in this exhibition as a compelling form of creative resistance and storytelling. Each quilt becomes a voice—individual yet interconnected—offering insights into the struggles, aspirations, and innovations that have shaped the United States. Fabric of a Nation situates fiber arts within broader national conversations about memory, citizenship, and inclusion, affirming the quilt’s role in chronicling America’s ongoing transformation.

Recent debates over transgender rights and cuts to federal arts funding underscore the exhibition’s contemporary relevance. Events like the ACLU’s Freedom to Be installation—featuring panels sewn by trans individuals on the National Mall—mirror the kind of narrative activism at the heart of this show. Fabric of a Nation is both a celebration of overlooked voices and a call to preserve the creative expressions that capture them.

A Tapestry in Seven Acts: Structure and Scope

Organized into seven thematic sections, the exhibition spans the 18th century to the present day. It includes works by Black, Latinx, Indigenous, LGBTQIA+, and immigrant artists, alongside comparative examples from Britain and India. This international context expands the dialogue, highlighting quilting’s global threads while reinforcing its uniquely American manifestations. As institutions face the repercussions of federal grant eliminations—jeopardizing the conservation of thousands of historic textiles—the exhibition emphasizes the urgency of safeguarding these cultural artifacts.

Each thematic section integrates visual richness with historical context, making the exhibition both intellectually rigorous and emotionally resonant. The quilts collectively chart America’s evolution, offering a tactile, deeply human archive of the nation’s shifting ideals and unresolved tensions.

The exhibition opens with the questions, “What is American? Who is American?” In response, two works explore voting rights as a measure of citizenship and freedom. A suffrage-era quilt reflects the historic struggle for women’s enfranchisement, while Irene Williams’s Quilt: Vote, Housetop Variation (1975) transforms fabric into a forceful act of civic engagement. These pieces speak directly to current debates over voter access and equity, reinforcing the enduring importance of democratic participation.

Unseen Hands: Honoring Invisible Labor

Unseen Hands examines the labor behind early quilts, often produced by anonymous makers. One striking example, the Whole Cloth Quilt (1750–1800), embodies the brutal legacy of slavery. Its materials—cotton and indigo—were cultivated and processed by enslaved African laborers. Though aesthetically refined, the quilt’s origins prompt a critical reflection on exploitation and systemic injustice. This section highlights the often-erased contributions that underpin American society, resonating with current discussions on reparations and racial equity.

As the Industrial Revolution transformed textile production, quilting retained its status as a personal and expressive art form. Crafting a Nation showcases quilts from the mid-19th century that combine machine-made materials with handmade techniques. These works reveal how traditional craftsmanship persisted amid rapid modernization. They also capture stories of westward expansion, women’s economic agency, and the social dislocations accompanying industrial progress. This historical moment parallels today’s concerns about automation, the decline of local industries, and the revival of artisanal practices.

Fabric of a Nation: Conflict Without Resolution

Conflict Without Resolution addresses some of the darkest chapters in American history. The Zouave Quilt (1863–64) romanticizes Civil War valor, while Carolyn Mazloomi’s Strange Fruit II (2020) confronts the lingering legacy of racial violence. Named after Billie Holiday’s anti-lynching song, Mazloomi’s quilt is a powerful indictment of systemic racism. This section echoes current social movements demanding justice and accountability, bridging historical trauma with present-day activism.

The section Quilts as Art charts the elevation of quilts from domestic necessity to recognized artistic form. Beginning in the late 19th century, quilts appeared at events such as the 1876 Centennial International Exposition, marking their entry into public artistic discourse. This shift challenges the hierarchy between fine art and craft, aligning with ongoing efforts to diversify art institutions and validate previously marginalized expressions. Today, quilts are increasingly viewed as complex visual texts—rich in symbolism, narrative, and technique.

Modern Myths: Deconstructing Americana

Modern Myths interrogates 20th-century constructions of quilting as a nostalgic, quintessentially American tradition. Amish quilts, for example, were celebrated for their simplicity and authenticity, yet this idealized view often masked the complexity of their makers’ lives. The section critiques romanticized representations of rural and immigrant communities, inviting a more nuanced engagement with American heritage. The recent revival of interest in the Quilts of Gee’s Bend exemplifies this shift, recognizing these works as sophisticated commentaries on history and identity, not merely charming relics.

The final section, Making a Difference, features quilts as tools for protest, remembrance, and affirmation. Contemporary works address themes such as environmental justice, feminism, systemic racism, and gun violence. Bisa Butler’s To God and Truth (2019), for example, reimagines a historical photograph of a Black baseball team from Morris Brown College using Kente cloth and Nigerian batik. The result is a vibrant, emotionally charged tribute to Black legacy and excellence. Quilts here function as acts of visual advocacy—expressing solidarity, grief, resistance, and hope.

This section draws parallels to contemporary quilt-ins and protest quilts like the Freedom to Be installation and grassroots efforts in Utah. These modern movements echo the AIDS Memorial Quilt tradition. Together, they emphasize quilting’s ongoing role in civic dialogue, collective healing, and queer and trans visibility.

Local Resonance, Global Fabric

In a thoughtful extension of the MFA exhibition, the Frist Art Museum added local discourse to topical issues inherent in Fabric of a Nation. Its Art in the Atrium series showcases works by Nashville-based artists Shabazz and Ashley Larkin. Their quilts explore the Black male experience, intergenerational ties, and community resilience. These local voices expand the exhibition’s impact by connecting national themes to regional narratives. They reinforce the idea that America’s story is made of countless individual contributions. Their inclusion affirms the power of art to foster belonging and bridge cultural divides.

While rooted in American experiences, Fabric of a Nation includes comparative quilts from India and Britain, highlighting quilting’s global dimensions. These works reveal the intertwined histories of textile production, trade, and colonialism. By incorporating a transnational perspective, the exhibition challenges insular notions of national identity. Additionally, it invites visitors to consider the shared human impulse to create meaning through fabric.

Fabric of a Nation: Preservation in Peril

Despite growing recognition of quilts as cultural treasures, preservation efforts remain precarious. In 2025, the Berkeley Art Museum lost a $460,000 IMLS grant intended to conserve 1,500 African American quilts. Without alternative funding, half the collection may be at risk. Similar shortfalls across the country have prompted lawsuits and emergency campaigns. These funding crises reinforce the exhibition’s urgent message: that cultural memory, especially from marginalized communities, requires active and sustained support.

A Living Archive of the American Spirit

Fabric of a Nation is more than an exhibition; it is a dynamic meditation on identity, memory, and resistance. Each quilt acts as a narrative fragment, stitched into the larger story of America. The show invites viewers to engage with complex histories and present struggles through the tactile intimacy of cloth. It affirms quilting as both a historical record and a living medium of protest, community, and creativity.

In an era marked by polarization and cultural flux, this exhibition offers a powerful reminder of art’s capacity to unite, challenge, and heal. For historians, artists, educators, and socially engaged citizens, Fabric of a Nation offers a powerful lens for exploring the complex narratives of American identity, creativity, and social change—threads intricately woven through the art of quilting. It invites a necessary reckoning with the layered realities of American life, both past and present.”

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Instagram (Opens in new window) Instagram

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- More