ART REVIEW

Step into a new world where sculpture meets photography in Photographer as Sculptor, the bold inaugural show at Bruce Silverstein Gallery.

BY KAZEEM ADELEKE, ARTCENTRON

NEW YORK, NY – The Bruce Silverstein Gallery ’s inaugural exhibition at its new location, Photographer as Sculptor, Sculptor as Photographer, marks a reflective moment in contemporary curatorial practice. By challenging conventional distinctions between sculpture and photography, the exhibition uncovers a rich, often underexplored dialogue between form and image. Featuring seminal works by influential artists from the 19th and 20th centuries, the show invites viewers to reconsider the boundaries—and overlaps—between these two artistic disciplines.

Featuring legendary names such as Constantin Brâncuși, Auguste Rodin, Henry Moore, David Smith, and Man Ray, alongside the photographic genius of Bernd and Hilla Becher, Imogen Cunningham, and Edward Weston, the exhibition uncovers crucial connections. It highlights the sculptural essence inherent in the photographic image. Simultaneously, it exposes the photographic impulse within sculptural form.

Photography as Sculptural: The Transformative Lens

From its earliest days, photography transcended mere documentation. It was a transformative process for sculptors. Auguste Rodin, renowned for his revolutionary approach to form, viewed photography as an extension of his chisel. He manipulated light and shadow with tactile intentionality. This crafting of images mirrored the textural complexity of bronze and the patinated hues of oxidized metal. Rodin’s application of potassium dichromate coating imbued prints with painterly qualities—deep greens and earthy browns. These enriched the visual language of his sculpture.

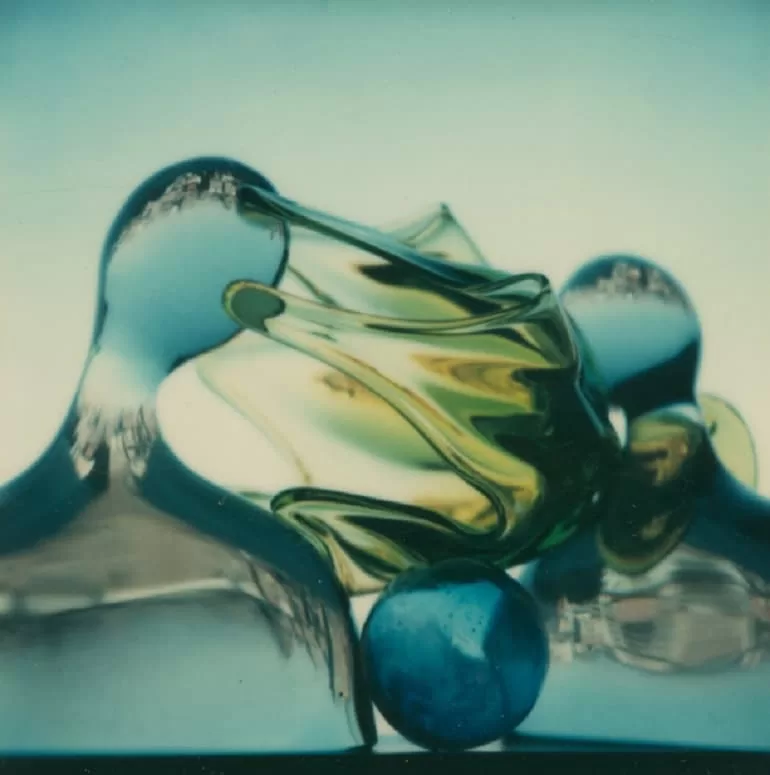

Constantin Brâncuși further refined this practice. His photographs blurred the boundaries between objects and auras. Through his lens, sculptures shimmered with abstraction. They became ephemeral impressions as much as physical entities. Brâncuși captured reflections, movement, and changing light conditions. He treated photography not as documentation but as a continuation of the sculptural act. Here, shadow became substance, and form danced with absence.

Photographer as Sculptor in Context: Smith and Moore

The photographic work of David Smith offers compelling evidence of sculpture’s responsive relationship with its environment. Smith’s steel sculptures, photographed amid the open fields of his Bolton Landing home, assert their presence against vast landscapes and sweeping skies. His photographs are not static records. They are deliberate compositional studies. In these, reflection, texture, and negative space extend sculptural thinking. Smith’s lens animates these abstract forms. It reveals them as monumental sentinels that command their space.

Similarly, Henry Moore utilized photography to manipulate perspective and perception. He often exaggerated the scale and monumentality of his pieces. Moore placed small maquettes against neutral backdrops or nestled them into the greenery of Hertfordshire. He employed tight cropping and dramatic angles. These rendered intimate sculptures as monumental, abstract expressions. His framing choices exposed internal voids and undulating surfaces. They evoked associations ranging from prehistoric rock formations to modernist architecture.

Photographers as Sculptors: Framing Form and Texture

The exhibition extends beyond sculptors who photograph. It also elevates photographers who sculpt with light, composition, and subject. Karl Blossfeldt, with his stark botanical studies, exposed nature’s architectural precision. His works draw visual parallels to Art Nouveau and Constructivist sculpture. He treated seed pods, stems, and leaves as if chiseled in marble.

Imogen Cunningham advanced this dialogue. She used cropping and shadow to render floral forms as sensual, tactile sculptures. In Amaryllis (1933), a single leaf cleaves space with sleek precision. Its edge glows white against rich blacks. This appearance emulates the sheen of polished steel or the curves of modern sculpture. In her images, the natural and the synthetic converge—plants become artifacts, and artifacts take on a life of their own.

Bernd and Hilla Becher offered yet another perspective. Their rigorous typologies of water towers, blast furnaces, and coal bunkers transform industrial architecture into a minimalist sculpture archive. By standardizing perspective and scale, they stripped these structures of context. They emphasized form—cylinders, cones, and grids. They presented them as monolithic sculptures shaped by utility and time.

Sculptural Eroticism and Abstraction

Edward Weston’s early 20th-century nudes—particularly the iconic portrait of Anita Brenner—render the body as a soft, sculpted landscape. Flesh abstracts into undulating contours that echo Jean Arp’s biomorphic forms. Light and isolation become tools of transformation. Weston distills human anatomy into its essence—sculpture in skin.

Bill Brandt, equally captivated by the body’s forms, used bold contrast and extreme angles. He crafted nudes that resembled Moore’s monumental bronzes. His approach imbued the human figure with both mystery and weight. It emphasized curvature, shadow, and negative space.

Barbara Morgan, in contrast, infused photography with motion. Her dynamic compositions of dancers like Martha Graham slice through stillness. These images carve motion into the frame. They suggest that movement itself can be sculpted. Light trails and frozen gestures become chiseled forms, momentarily held in time’s grasp.

Man Ray: The Alchemist of Form and Vision

Man Ray stands among the most radical experimenters. He redefined how photography could simulate, distort, and become sculpture. From solarizations and rayographs to surreal reframings of classical busts, he revealed the camera’s potential to alter perception. In L’homme, for instance, ordinary objects—an egg tray, clothespins—are lit and composed as if they were Cubist sculptures. These found forms, stripped of their function, become phantasmagoric figures. They exist in a liminal space between objecthood and artifice.

Man Ray’s manipulation of visual expectations challenges viewers. He prompts the questions: Is the object more real than the image? Or is the photograph the final sculptural act—its flattened form holding infinite dimensionality?

A Unified Aesthetic Vision in Photographer as Sculptor

Photographer as Sculptor, Sculptor as Photographer is more than an exhibition—it is a curatorial thesis on the fluidity of artistic identity. It argues for a flexible understanding of visual disciplines. Photography and sculpture converge not in opposition but in creative synergy. By juxtaposing classical, modernist, and avant-garde works across medium boundaries, the exhibition at Bruce Silverstein Gallery charts a radical redefinition of visual art.

This new direction for the gallery signals an embrace of interdisciplinary thinking. Artists across generations and geographies echo each other’s explorations of form, light, space, and materiality. It offers a template for rethinking medium specificity. Instead, it posits a more inclusive framework of visual language—one that privileges vision over vessel.

Form Reimagined Through the Lens

As we traverse this groundbreaking exhibition, one truth becomes clear: photography and sculpture are not isolated practices. They are two perspectives within the same aesthetic continuum. Seen through this lens, the camera becomes not just an eye but a chisel. The sculpture becomes not just an object but a captured act of seeing. In bridging these worlds, Photographer as Sculptor, Sculptor as Photographer redefines how we understand and experience the visual arts.