ART & DESIGN

Julie Buffalohead, The Noble Savage, 2022. Oil on canvas, 52 x 84 1/4 inches / 132.1 x 214 cm. This is one of the paintings through which indigenous perspectives challenge colonial narratives. Courtesy of Silverman and Sarah Thornton, San Francisco

Experience how Indigenous Perspectives are redefining history in bold art exhibitions that take a stand against colonial narratives at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

BY KAZEEM ADELEKE, ARTCENTRON

BALTIMORE, MARYLAND-A critique of hegemonic Western curatorial practices is at the heart of nine seminal art exhibitions currently at the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA). These exhibitions are part of the Preoccupied: Indigenizing the Museum project, an ambitious initiative designed to reform museum practices by integrating Indigenous perspectives and challenging entrenched colonial narratives.

The Preoccupied project addresses the historical marginalization and subjugation of Indigenous artists and their work by foregrounding these perspectives within a museum context that traditionally privileged Western viewpoints. Each of these nine exhibitions confronts and critiques the power dynamics between Western institutions and Indigenous cultures, providing a platform for artists who have long been pushed to the periphery.

Revisiting Colonial Narratives through Indigenous Art

In essence, these nine exhibitions scrutinize and deconstruct the oppressive colonial narratives historically shaping museum practices. By prioritizing Indigenous voices and perspectives, these shows offer a counter-narrative to the often one-sided historical accounts that have dominated mainstream art institutions. More importantly, they challenge conventional power structures and reframe the dialogue around art and cultural representation.

The nine art exhibitions at the BMA feature exceptional drawings, paintings, sculptures, films, and art installations that are compelling in their narratives and vividly articulate neglected histories of Native people. The works amplify the voices of their creators, questioning and reshaping the conventional perceptions of Native peoples’ significant contributions to North American history.

1. Dyani White Hawk: Bodies of Water

Dyani White Hawk: Bodies of Water is a profound exploration of Sičáŋǧu Lakota artist Dyani White Hawk’s work. The artist challenges traditional art history by validating craft and historical artifacts as essential components of artistic discourse. In the John Walter Rotunda, the art exhibition highlights White Hawk’s Carry series, which includes both new and existing sculptural pieces. It features large copper buckets and ladles embellished with glass beads and long fringes, resembling tree roots. These pieces are juxtaposed with historic Lakota items from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection. Together, they emphasize the synergy between art, function, and cultural heritage.

Leila Grothe, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art, and Dare Turner (Yurok Tribe), Curator of Indigenous Art at the Brooklyn Museum, curated the exhibition. With support from Curatorial Research Assistant Elise Boulanger (Osage Nation), the exhibition invites visitors to engage with the delicate artwork respectfully and thoughtfully. The exhibition runs through December 1, 2024.

2. Caroline Monnet: River Flows Through Bent Trees

The Caroline Monnet: River Flows Through Bent Trees exhibition is in the Contemporary Wing of the museum. It includes a new site-specific installation by Caroline Monnet (Anishinaabe/French). Monnet’s work melds influences from eel trap pots used by the Chesapeake Bay Indigenous people with traditional Anishinaabe longhouses. This installation interacts with the museum’s architecture and asserts and reflects Indigenous presence through resonant forms. Caroline Monnet underscores the commitment to advancing Indigenous representation. It is on view through December 1, 2024.

3. Don’t Wait for Me; Just Tell Me Where You’re Going

This important exhibition features short films that interrogate generational memory and Indigenous perspectives. Guest curator Sky Hopinka brings together a diverse selection of films that explore themes of time, movement, and landscape. They honor the collective journey of Indigenous peoples. Don’t Wait for Me; Just Tell Me Where You’re Going includes works by Lindsay McIntyre (Inuk), Olivia Camfield (Muscogee Creek Nation), and other notable artists.

Lindsay McIntyre’s “Seeing Her” is one of the thought-provoking pieces in this exhibition. The 3:30-minute silent film highlights the generational significance of beadwork. Using hand-processed Super 16 film, the artist captures the intricate details of her great-grandmother’s amauti. There is also “We Only Answer Our Landline” by Olivia Camfield and Woodrow Hunt. The film explores themes of cultural alienation through a blend of family snapshots and archival footage, set to music by Black Belt Eagle Scout. Don’t Wait for Me; Just Tell Me Where You’re Going emphasizes the shared experiences of Indigenous communities. It runs through December 1, 2024.

4. Enduring Buffalo

Indigenous Perspectives on Native Americans and Buffalo

Enduring Buffalo highlights the significance of buffalos in Plains Indigenous cultures and the impact of their near extinction. Buffalos are important in Native American culture as they symbolize strength and resilience. For thousands of years, Native Americans have relied on bison for food, clothing, shelter, and tools. They also use every part of the animal by incorporating it into their spiritual practices. The mass killing of bison in the 1800s severely disrupted Native American societies, leading to widespread devastation. Their loss profoundly impacted the survival and traditions of the Plains tribes. Enduring Buffalo features works by the Pawnee Bear Doctors Society, Making Medicine (Cheyenne), and other renowned artists. Their work addresses historical efforts to eradicate the buffalo and its effects on Native art-making practices. The collection reflects the enduring cultural and spiritual importance of the buffalo in Plains Indigenous art and identity.

‘Cheyenne Hunting Buffalo’

One notable work illustrating the connection between Native Americans and buffalo is “Cheyenne Hunting Buffalo” by Bear’s Heart (Cheyenne). This ink and watercolor piece on woven paper portrays Native Americans on horseback, actively pursuing a herd of buffaloes. With bows and arrows, they strive to get what they need. The scene is dynamic and dramatic. It captures the energy and intensity of the chase. As some riders fall from their horses, others continue the pursuit with unwavering determination.

This two-page illustration is part of a ledger art book featuring sketches by Making Medicine, Bear’s Heart, Buffalo Meat, Etah-dle-uh Doanmoe, Koba, and other Kiowa and Cheyenne prisoners of war held at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida. These sketches provide a vivid depiction of Native American life and struggles during their internment, which occurred as part of the U.S. military campaigns against the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Arapaho, and Comanche Nations during the Red River War of 1874–1875.

5. Finding Home

Finding Home explores the dynamic relationship Native peoples have with land, home, and sanctuary. Native peoples have a profound and multifaceted relationship with the land, viewing it as “Mother Earth.” It is central to their cultural and spiritual practices. They practice reciprocity by taking only what they need and giving back through ceremonies and rituals. This symbiotic relationship reflects a deep sense of belonging, identity, and connection to their ancestors. It is particularly crucial for preserving their cultural heritage and ensuring sustainable coexistence.

This exhibition features artists such as Tom Haukaas (Lakota and Puerto Rican) and Marie Watt (Seneca Nation and German-Scot). It underscores the resilience and adaptability of Native artists in preserving their cultures and sense of home amidst modern pressures. More importantly, it highlights how traditional values intersect with contemporary practices, enriching the narrative of Native art.

One of the prominent works in this exhibition is I Awake To You 2023. This film by the artist Meryl McMaster draws on the numerous references to trees the artists found in diaries and old photographs. She reflects on their significance in Red Pheasant’s prairie environment and to her family. Poplar trees, abundant in the area, provided essential resources for warmth, shelter, ceremonial lodges, economic livelihood, and traditional medicine for the artist’s family. I Awake To You highlights the trees’ symbolism, paralleling the resilience and survival of the artist’s ancestors over three generations. The film is one of the new works in the Baltimore Museum of Art Acquisitions. The exhibition is on view through December 1, 2024.

6. Illustrating Agency

Illustrating Agency examines how Native artists have challenged settler-defined notions of authenticity. Featuring influential artists like Stephen Mopope (Kiowa) and Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache), this exhibit showcases how Native artists have increasingly represented their communities on their own terms. By addressing modern Native experiences and critiquing stereotypes, the exhibition redefines the perception of Native art and identity. Julie Buffalohead’s “The Noble Savage,” for instance, examines identity, cultural heritage, and the intersection of indigenous and European cultures. Combining traditional Native American imagery with contemporary pop culture, she critiques Eurocentric views on civilization and savagery. In a strongly woven narrative, Buffalohead uses her work to reclaim and reinterpret Native American narratives, highlighting their resilience and complexity. Illustrating Agency is on display through December 1, 2024.

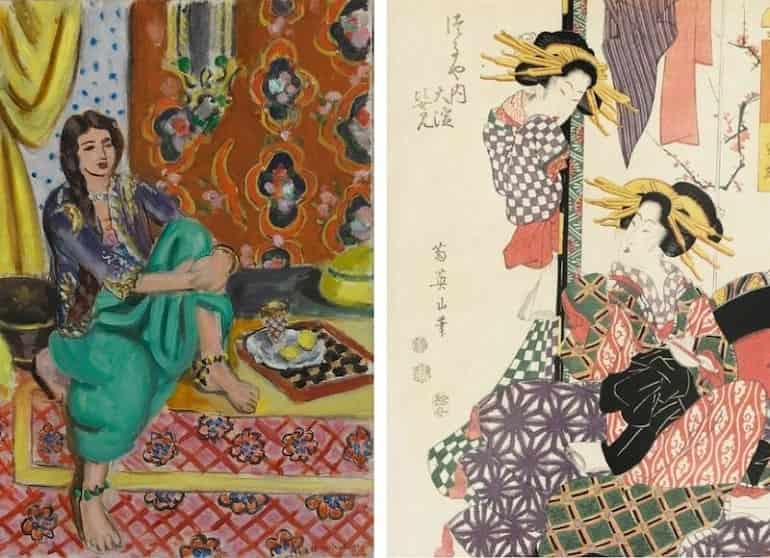

7. The Art of Pattern: Henri Matisse and Japanese Woodcut Artists

The Art of Pattern: Henri Matisse and Japanese Woodcut Artists explores the use of color and pattern in art through a comparative analysis. It features Matisse’s works from the 1920s and 19th-century Japanese woodcut art by artists such as Kikugawa Eizan and Keisai Eisen. The exhibition accentuates how both Matisse and Japanese artists utilized decorative elements to enhance their compositions. This approach is particularly evident in Utagawa Kunisada’s print “Geisha Standing beside the Entrance of the Umewaka Restaurant” (late 1820s), which depicts a stylish woman outside a restaurant, reflecting a common trend in Japanese prints.

This show bridges cultural and temporal divides, offering a rich visual experience through vibrant patterns and dynamic settings. However, unlike Matisse, who often placed his subjects in confined spaces, these artists feature female figures in public settings, dressed in elaborate robes with symbolic patterns. The exhibition, including an ornately patterned obi, shows how Japanese Woodcut prints not only advertised businesses and influenced fashion but also presented an idealized world of beauty and pleasure, offering a glimpse into the aesthetics of two distinct cultures and eras. The exhibition is on view through January 5, 2025.

8. Laura Ortman: Wood that Sings

The exhibition Laura Ortman: Wood that Sings features Laura Ortman’s (White Mountain Apache) innovative video work, ‘My Soul Remainer.’ It also includes a historic Apache violin by Amos Gustina from the BMA collection. Ortman’s video combines classical music with modern composition. It challenges traditional norms and highlights the significance of the Apache violin in preserving community traditions. In ‘My Soul Remainer,’ Laura Ortman performs her violin across various southwestern U.S. landscapes. She blends her original score with a piece by Felix Mendelssohn to create an ethereal composition. Her composition helps assert Native autonomy in the context of Western classical music.

Wood that Sings reflects on the role of music as a vital link within Indigenous communities. It honors cultural continuity and heritage by connecting the past, present, and future. Ortman’s work challenges misconceptions about Apache musical instruments, reaffirming their deep historical roots and Indigenous ingenuity. This exhibition demonstrates the ongoing relevance of Indigenous cultural practices within contemporary art. It runs through January 5, 2025.

9. Dana Claxton: Spark

established with exchange funds from gifts of Dr. and Mrs. Edgar F. Berman, Equitable Bank, N.A.,

Geoffrey Gates, Sandra O. Moose, National Endowment for the Arts, Lawrence Rubin, Philip M. Stern, and Alan J. Zakon, BMA 2023.113. c Dana Claxton. Courtesy of the artist

Understanding Contemporary Native Artistic Expression

Dana Claxton: Spark showcases Dana Claxton’s (Wood Mountain Lakota First Nations) large-scale, backlit color transparency photographs. The artist refers to these works as “fireboxes” to evoke elemental energy and Indigenous sensibilities. This solo exhibition also includes Claxton’s vibrant photographic work, featuring works from her Lasso and Headdress series. Complementing these works are Native physical objects from her imagery and historical Indigenous art. They include traditional regalia, moccasins, beaded pouches, and cradleboards from the BMA collection that Claxton chose to enhance the thematic focus of the show. This integration of the visual and physical objects emphasizes the relationship between cultural objects and their significance. But more importantly, it contextualizes Claxton’s work with items from the BMA’s historic Native art collection. Dana Claxton: Spark fosters a deeper understanding of contemporary Native artistic expression. It continues through January 5, 2025.

Preoccupied: Indigenizing the Museum project is eye-opening. Historically, museums have perpetuated colonial hierarchies by exhibiting artifacts and art from colonized regions without considering their cultural contexts. This practice, rooted in colonialism, underscores the urgent need for museums to reassess and reform their approaches to collections and representation. Contemporary artists are questioning and deconstructing these outdated narratives. They address historical injustices and the misrepresentation of cultures. With their works, they are redefining how museums present and interpret collections. But more importantly, in addition to their critique of museum practices, they are also proposing alternative frameworks that embrace diverse cultural expressions and correct past missteps.

Indigenous Perspectives: Decolonization of Museums

Preoccupied proves that the contributions of contemporary artists are vital to the decolonization of museums. For decades, Native artists have actively challenged the colonial legacies embedded in museum practices. The works in these nine exhibitions challenge oppressive colonial narratives and foster a more inclusive approach to cultural representation. These critical perspectives are increasingly shaping the global conversation around museum decolonization. Exhibitions and artworks challenge local and international museum practices, pushing for more inclusive and equitable approaches. As museums strive to move beyond their colonial past, integrating these contemporary viewpoints is essential for creating spaces that truly respect and celebrate the richness of global cultures.

The curators of these exhibitions deserve commendations for their counter-hegemonic commitment to curatorial practices. Working in institutions that assert dominance of the Western center and efforts to confront subjugating cultural narratives must be exasperating. Nonetheless, these nine exhibitions at the Baltimore Museum of Art collectively reflect a commitment to integrating Indigenous perspectives into museum practices. More importantly, they challenge colonial narratives by providing alternative perspectives that highlight the rich, diverse histories and contributions of marginalized Indigenous voices. In a meaningful and respectful manner, they offer visitors a unique opportunity to engage with Indigenous art and culture, reshaping how these narratives are represented and understood.