ART NEWS

Veterans Tell Traumatic Stories of War, Rape, and PTSD

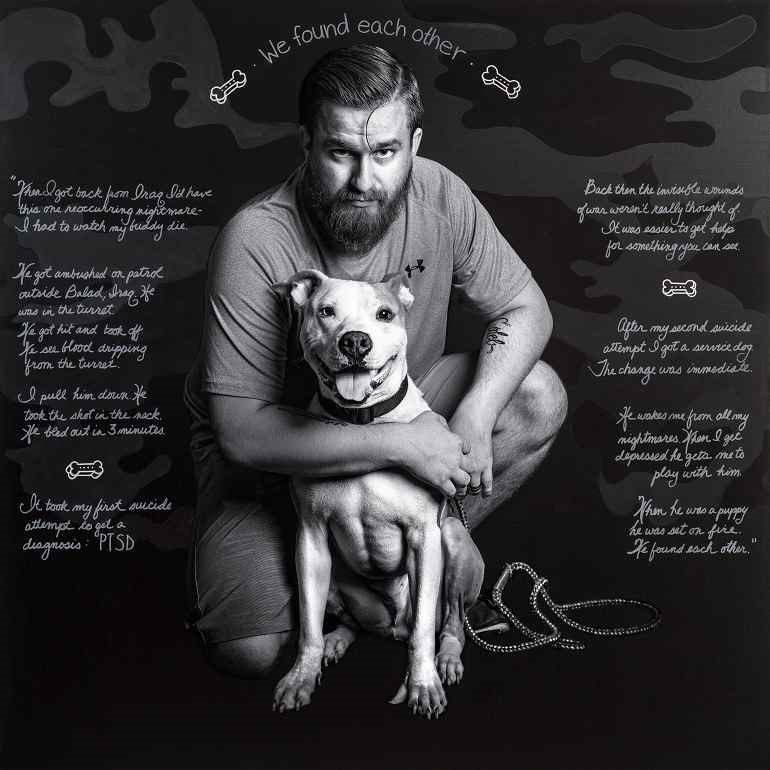

posted by ARTCENTRONA portrait of Mike is one of the works in Depicting the Invisible, an exhibition of works by Susan J. Barron celebrating American veterans.

ART REVIEW: Traumatic stories of war, rape, and PTSD were at the center of Depicting the Invisible, an exhibition of works by Susan J. Barron celebrating American veterans

BY KAZAD

NEW YORK, NY-The impact of war on veterans’ is deeper than the visible physical injuries we all see. Many veterans of Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and other wars will tell you that injuries of war are deeper than most people can imagine. Beyond the physical injuries, there are also traumatic injuries that are invisible but devastating.

Veterans: PTSD and Suicide

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is an invisible injury that has led to many veterans taking their own lives. Recent data shows that an average of 22 veterans commits suicide every day in the United States due to PTSD. Further complicating veterans’ issues is poverty and homelessness.

With the increase in the number of veterans committing suicide, it is not surprising that many people are doing their part to bring attention to PTSD and its impact on American war veterans. One of them is Susan J. Barron whose series of large-scale portraits of American veterans suffering from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was on display at the HG Contemporary Gallery in New York. Titled Depicting the Invisible, the exhibition featured a series of large-scale black and white portraits of American veterans suffering from PTSD. In all, there were 14 portraits.

In addition to the portraits of the veterans, each work is inscribed with traumatic stories of these brave American heroes. Each story is a deep look at the experience of these veterans as they deal with PTSD and other social issues. However, their stories did not start with PTSD: it all began in the theaters of wars: Iraq and Afghanistan.

The portrait of Mike allows an insight into the harrowing experience of American soldiers on the war front. In the center of the painting is a portrait of Mike with all his tattoos memorializing events in his life. He gazes into space with a tinge of smile on his lips.

Mike is a handsome guy. He is a well-groomed man who pays great attention to his look. His hair, beard, and mustache are carefully trimmed and nurtured. Mike’s eyes also spackle gleefully in this captivating portrait. Charismatic as the portrait appears, there is more to Mike than meets the eyes. He suffers from PTSD.

The story of how Mike became a victim of PTSD is well- inscribed around his portrait. It all began one day while on patrol with two other soldiers in the Anbar Province, Iraqi. As they drove through the city, a strange and ominous feeling overtook Mike. Moments later, disaster struck. “An IED went off.” The impact of the blast was devastation. Mike explains: “It threw me 60ft in the air, I can’t hear. My arm is badly bleeding. I realize the 2 other guys in the humvee are gone”.

The attack was damaging physically and emotionally, but Mike was determined to continue fighting. When the army tried to send him home, he would not let go. “I signed up to give my life to my country and I had not done that yet so I am staying”. Eventually, Mike returned home.

But, soon after returning home, he began to exhibit symptoms of PTSD. The scars of war, including the death of his friends on the battlefield burdened his heart, causing PTSD. Although Mike has been getting treatment for his PTSD, and come a long way from the attack in the Anbar Province, he does not think any treatment can totally take away the invisible war injuries. For him, PTSD victims must accept that the affliction is a part of their lives and “you’ve got to accept it is what it is”.

Derek: Saved by Phoenix

For many veterans, accepting that PTSD is an integral aspect of their lives takes time and serious intervention because the experience of war lingers forever. The experience of Corporal Burke is illuminating.

In this portrait, Corporal Burke looks stern, strong, and very stylish. A strand of hair plays on his forehead, showing his contemporary fashion sensibilities. In front of him is his pit bull, Phoenix. From the way Corporal Burke is holding Phoenix, it is clear that there is a strong bond between them. Together, they gaze at the camera as one.

The story of Corporal Burke is heartrending. It recounts the horror of war that is forever present in the life of American war veterans. His story began after experience the death of a friend in Iraqi. “I watched my buddy die,” he recalls. While on patrol in Balad, Iraqi, Corporal Burke and his friend were ambushed by insurgents, and a firefight ensued. During the fight, his friend was shot. “He was in the turret. He got hit and took off. We see blood dripping from the turret.” When Corporal Burke pulled him down, he was overwhelmed by the horror before him. “I pull him down. He took the shot in the neck. He bled out in three minutes,” he explained.

When Corporal Burke returned home from Iraqi, the horror of the war formed a loop in his mind. “When I got back from Iraq, I’d have this one recurring nightmare—I had to watch my buddy die.” Several times, he tried committing suicide. The saving grace for him is a dog called Phoenix. He got better after getting a service dog that has since been his companion. It has helped him through troubled times. No doubt, Phoenix is an apt name for the dog that brought him back from the brink. “We found each other,” he notes.

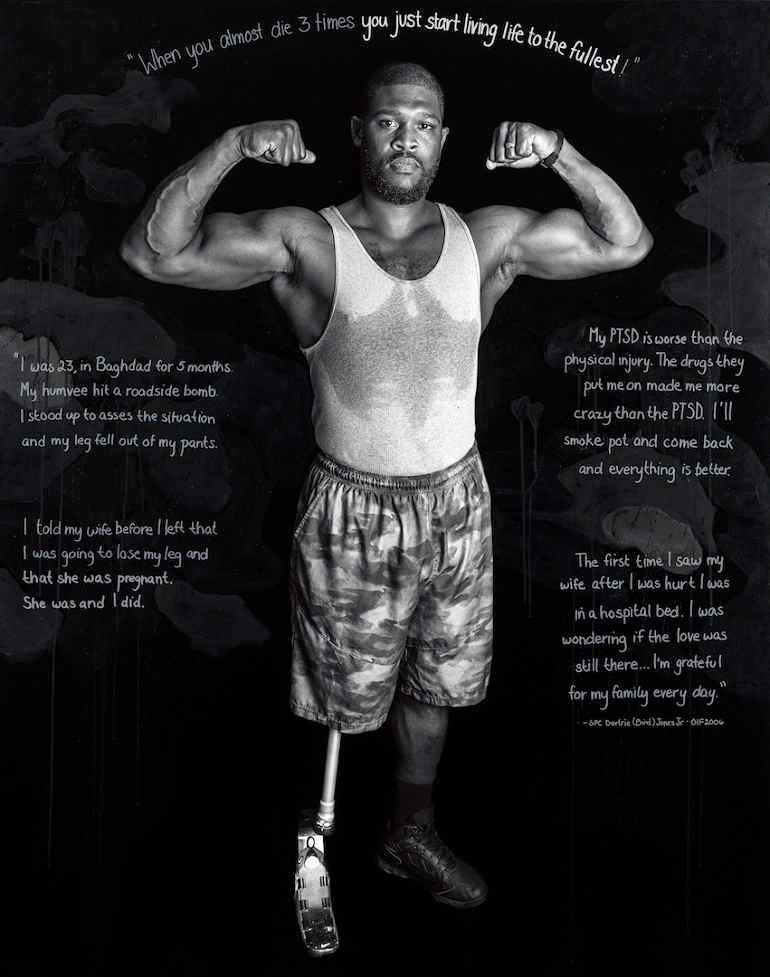

Bird: “My PTSD is worse than the physical injury.”

American soldiers are trained to be the best in the world. Besides their technical skills, many take the time to build their bodies. The portrait of Bird shows a proud American soldier who made due diligence in building his body. With arms raised, he flexes his bulging biceps like a WWE wrestler. His sweat-stained undershirt shows his absolute devotion to keeping his body in shape.

Bird is a strong and confident man, and he must have taken those qualities to the war front with him. However, war goes beyond confidence: War is unpredictable and Bird knows that very well now. While on patrol in Baghdad, his Humvee hit a roadside bomb. The blast was sky high and the consequence horrifying. “I stood up to assess the situation and my leg fell out of my pants,” he explained. Bird was only 23 when he lost his leg.

Today, Bird wears a prosthetic where his right leg used to be. Nonetheless, losing a limb has not eroded his confidence. In this portrait, Bird stands tall and proud. But, proud as he is, this American veteran continues to deal with the after-effects of war. “My PTSD is worse than the physical injury. The drugs they put me on made me more crazy than the PTSD,” he said.

The stories of war, injuries, and PTSD told by veterans are harrowing and traumatizing. However, these strong people take great pride in their service to the country. Sergeant Carter, for instance, puts it succulently. Sitting in a wheelchair, he reflects on his war injuries: “I’m paralyzed from the neck down for the rest of my life. I spent 16 months in a VA hospital, and I saw that it could be so much worse.”

Like many of the other veterans whose portraits were on display in this exhibition, the story of Sergeant Carter began with the deployment to Afghanistan as part of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF). Two months after deployment, his truck went off a bridge and he ended up at Walter Reed. The physical injuries were crippling.

In addition to the debilitating injuries sustained on that fateful day in Afghanistan, Sergeant Carter also suffers from PTSD. He began to see things soon after arriving home. “I saw people in the windows shooting at me but I know it can’t be real but I can’t accept it’s not real. It’s terrifying. That is a flashback. PTSD”. Although Sergeant Carter’s physical injuries landed him in a wheelchair, he prefers it over PTSD. “I would rather have physical injuries than mental injuries any day,” he notes.

Veterans Affairs

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs is at the core of ensuring that the veterans represented in this exhibition and other military veterans are adequately cared for as they recover from their physical and mental injuries. Its job includes ensuring that veterans get the best treatments available at Veteran Affairs Hospitals located across the country. The VA also continues to take care of their well-being after leaving the hospital.

No doubt, the role of Veteran Affairs is integral to the well being of military veterans. However, some of those represented in this exhibition did not hold back in their criticism of the VA. Sergeant Carter, for instance, thinks that VA is part of the problem many veterans are facing:

The biggest problem I see is the VA hands out opioids like it’s their job. Guys get hooked on opioids from the VA, get discouraged, lose their meds, start using heroin, and OD. It’s a shame to see vets make it through the hell of war and then die at home because they’re set up to fail by the VA.

This important exhibition reminds Americans of the role of the American military and the issues they confront even after leaving the service. Susan J. Barron’s photographs are elegant and depict these strong Americans who put themselves in danger to serve the country. Even so, the images also highlight the dangers of war and the impact of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder on veterans of different wars. Many of these artworks are conversational pieces and they add to the debate of how veterans are treated after they return home from their service in the war zones.

While their visible injuries are quickly treated, the invisible injuries like PTSD take time to heal. The consequence is that many end up committing acts of violence, including suicide. “The invisible wounds of war are just as devastating as the visible ones. My mission is to bring awareness to the PTSD epidemic and to provide a platform for veterans to share their stories,” notes Barron.

A key element of the show is an interactive work titled A Table for the Fallen. For this work, visitors were invited to sit and create personal tributes to fallen soldiers. Participants were filmed as they morn and celebrate friends and families who died in the service of their country.

Military Veterans: Rape and PTSD

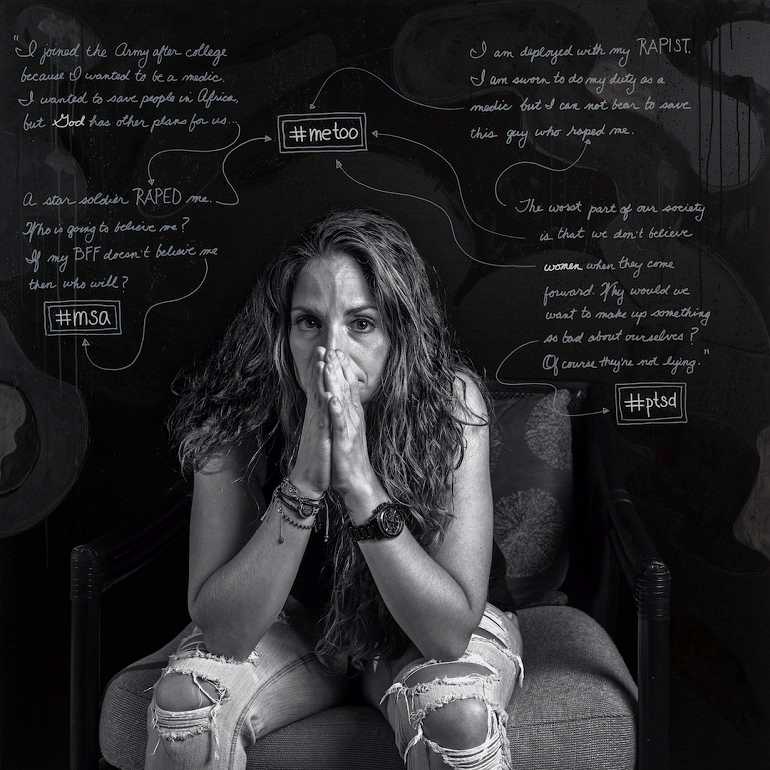

Majority of the works in this exhibition were focused on physical war injuries and the impact of PTSD resulting from veterans’ experiences in the war front. One of the works, however, touches on the cruel reality of rape in the military and consequences on female soldiers. At the center of this issue is Sergeant Trotter. The portrait of Sergeant Trotter tells a lot of stories. In this black and white portrait, she sits in an armchair with her elbows resting on her laps. She covers a part of her face with both palms of her hand.

Sergeant Trotter’s facial expression is riddled with meaning. As she gazes into space, her eyes are focused and piercing. The veins on her forehead attempt to bust through her skin, exuding a feeling of anger, frustration, and exasperation. This is the portrait of a woman at a crossroad.

Rena: “A star soldier raped me”

The story of Sergeant Trotter is that which many may be familiar with. She joined the army after college with the hope of becoming a medic and the desire to save people in Africa. She was devoted to fulfilling her goal and then she was raped by a soldier. “A star soldier raped me” she recalls. Adding salt to injury, many people did not believe her when she spoke out. “Who is going to believe me? If my BFF doesn’t believe me then who will? To make matters worse, Sergeant Trotter was deployed with the person that raped her.

The strain of dealing with being raped and serving along with her rapist resulted in PTSD. Even as Sergeant Trotter dealt with the internal conflict of her rape and confronting her rapist, she also struggled with the apathy among people when women report they had been raped. “The worst part of our society is that we don’t believe women when they come forward. Why would we want to make up something as bad about ourselves? Of course, they are not lying.”

Sergeant Trotter’s sense of powerlessness engendered an internal turmoil and conflict that caused her to question the ethics of her profession as a military medic. “I am deployed with my RAPIST. I am sworn to my duty as a medic but I can not bear to save this guy who raped me.”

This is the portrait of a strong confident woman broken by the trauma of rape. From her flowing long hair, torn jeans and bracelets, it is clear that this is a woman who can move mountains if she decides to do so. However, the trauma of rape puts her in a place of uncertainty.

Many women have spoken about the devastating traumatic effect of rape and PTSD, but people continue to doubt them. Sergeant Trotter is adding her voice to the cries of women who have been disparaged by the powers that be for letting the world know that they were raped or molested. In this era of the #metoo movement, women who have been raped or assaulted should speak up even if they will be condemned by the rich and powerful who throw their power in the face of the vulnerable.

Veterans Day

On this Veterans Day, it is important to celebrate our Veterans. Susan J. Barron’s photographs of the injured American soldiers show the horrors of war. Beyond the physical injuries, they also suffer injuries that are invisible but devastating. As many of them struggle to recover, they bring into focus the issue of opioid addiction, homelessness, poverty, and above all, suicide among veterans. While there is an acknowledgment that The US Department of Veterans Affairs has been doing a lot to address veteran issues, many people think VA should be doing more to help American soldiers returning from war.

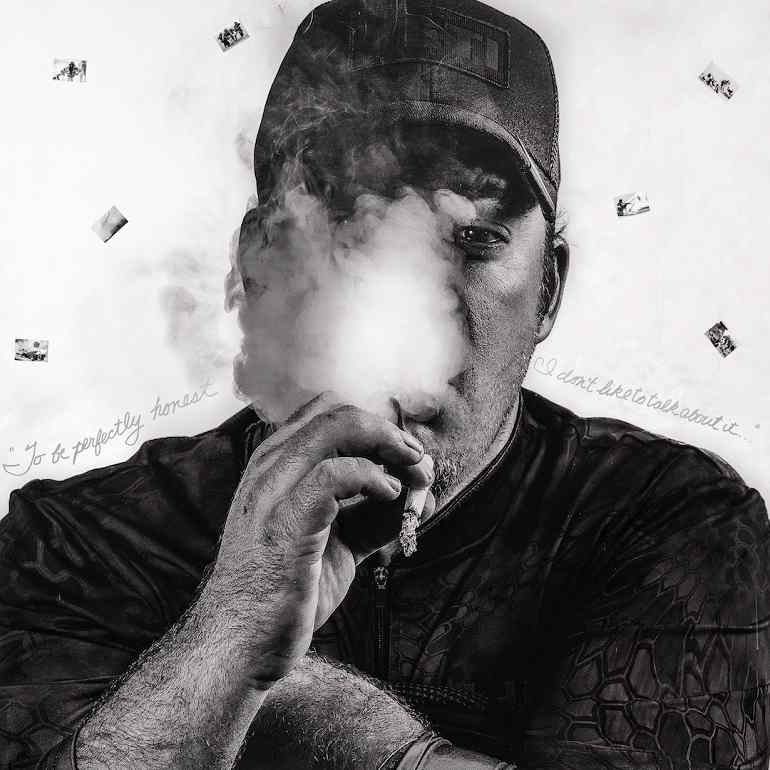

Hebert: To be perfectly honest, I don’t like to talk about it.

Do you want to celebrate a military veteran or veterans? Share your story with us or leave a comment.

Share this:

- Share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Share on Reddit (Opens in new window) Reddit

- Share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Share on Instagram (Opens in new window) Instagram

- Share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- More