ART

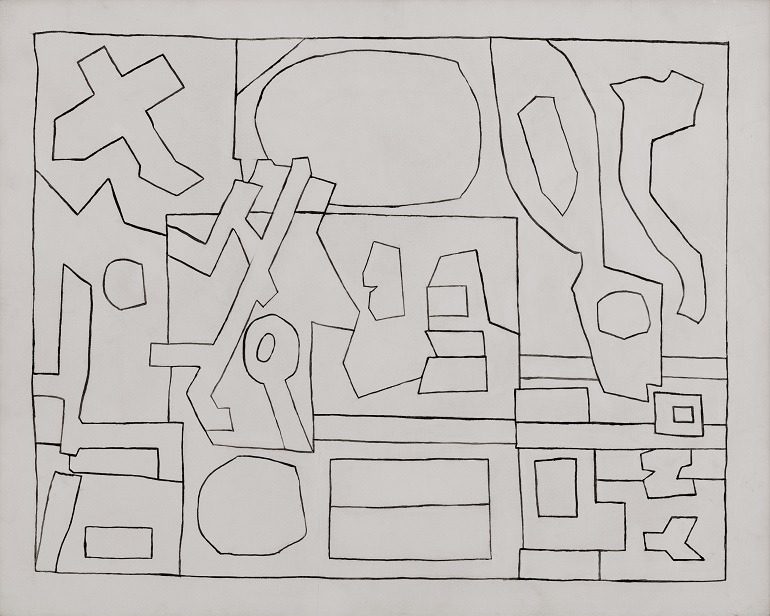

Untitled (Black and White Variation on Pochade), 1956-58, by Stuart Davis. CreditCreditAll rights reserved Estate of Stuart Davis/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY; Paul Kasmin Gallery

ART REVIEW: Stuart Davis black and white paintings on display at the Paul Kasmin Gallery reveal a restless artist constantly in search of new ways to express his creative ideas and thoughts.

BY KAZAD

NEW YORK, NY—Stuart Davis was a painter with high color sensibilities. His paintings are rich in reds, blues, greens, and many other colors intricately woven to dizzying actualizations. Influenced by street life, swing music, and jazz, Davis’ paintings are characterized by a confluence of bright vivacious colors, expressive lines, and repetitious shapes combined in a visual rhythm symptomatic of improvisation of jazz music.

For many years, there has been a particular focus on Davis’ colorful paintings. However, while many people are familiar with his colorful paintings, not many have had direct encounters with his black and white paintings. Those black and white paintings are the focus of a new exhibition at the Paul Kasmin Gallery in New York. Lines Thicken: Stuart Davis in Black and White features more than 25 large-scale black and white paintings by the artist done between the early 1920s and 1950s. Some of these paintings bring attention to a period when the artist was already slowing down and recycling earlier motifs that he called “beat-up subject matter”.

Lines Thicken: Stuart Davis in Black and White is the first exhibition in more than three decades devoted to Davis’ large-scale black and white works on canvas and paper. These are important paintings in the career of this celebrated American artist. For an artist already well known by the mid-1920s for his effervescent color, the black and white paintings were a drastic shift from the artist’s established artistic tradition.

Stuart Davis: A Bold Swing to Black and White

Stuart Davis’ swing from a vibrant palette to black and white was a bold step that spoke to his restless search for new ways of expressing his creative ideas and thoughts. More importantly, it brought to the fore the artist’s ability to deconstruct his work to the barest minimum, exposing his process to the viewers. As his son Earl Davis notes, his father’s work was rooted in drawing and not color.

Although Davis was the proponent of a color theory that captivated many, his trajectory had changed by mid-century. Instead of the vibrant color scheme that permeated his earlier works, his ideas had succumbed to a minimalist tradition that privileged lines over colors. As expected, lines became the keystone of his compositions. However, even in their simplicity, Davis’ lines are dramatic. The lines crisscross over each other creating a labyrinth of complex layers. They are a reminder of the dizzying qualities of his vivacious colorful paintings. Above all, the intricately woven, yet complex lines, speak to the restlessness of the artist in his pursuit of eloquent ways to express his creativity.

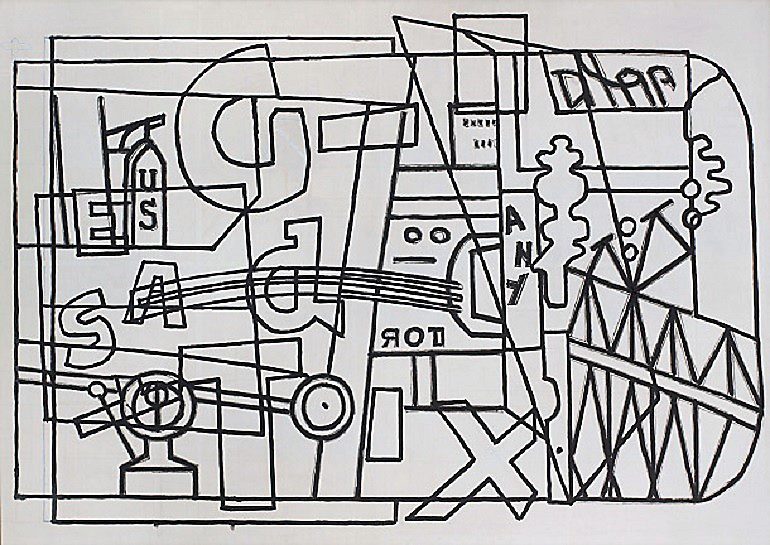

Stuart Davis, Letter and His Ecol. (Black and White Version), 1962. Casein on canvas, 24 x 30 inches, 61 x 76.2 cm. Image: Paul Kasmin Gallery. © Estate of Stuart Davis

The importance of drawing in Davis’ works is apparent in Letter and His Ecol. A casein on canvas, the piece is a black and white Version of another painting with the same title by the artist. The piece includes different shapes layered over each other in a way that creates depth, modulation, and intriguing cascading elements. There are circles, rectangles, squares, cubes, and amorphic shapes. On one side of the piece is the word “ONY”.

Although Letter and His Ecol has its origin in the painted version, this black and white piece stands by itself. Unlike its colored version, this Letter and His Ecol has depth and reveals the intricacies absent in the colored version. Looking at the black and white version of Letter and His Ecol, it is easy to conclude that one of the reasons Davis created the black and white version of his original painting is not just because of his theories, but also because the original did not adequately communicate his ideas and emotions.

Letter and His Ecol is part of Davis’ effort to make his paintings accessible to a wider audience. Through seriality and a resolute adherence to a restrained and meaningful vocabulary of shapes, he crossed many lines to foster a larger engagement with his works and process. Furthermore, Davis’ adherence to making his work available for a larger audience was also informed by his political views nurtured by his leading roles in organizations such as the Artists Union and The American Artists’ Congress.

Stuart Davis, Untitled (Black and White Variation on Windshield Mirror) c. 1954-64. Casein on canvas. H- 54 x W- 76 in. (137.2 x 193 cm). Credit line. © Estate of Stuart Davis/VAGA, New York

Untitled (Black and White Variation on Windshield Mirror) is another work that shows Stuart Davis ability to communicate the relevance of his work to a larger audience. More importantly, it shows the power of drawing not just as the fundamentals of Davis’ creative endeavor, but also as works of art on their own. Although Untitled is the offshoot of another painting of the same title, it is dramatic, illuminating, and intriguing. In the piece, lines intermingle with lines in dramatic overtures. Some lines are jagged while others are straight and curve. In the background and intermingling with the lines are letters cascading and floating through space. This is an arresting piece with a confluence of lines, shapes, and letter merging into a huge motif.

A Restless Soul: Stuart Davis Search for New Forms of Expression

A leading American modernist, Davis was very persistent in propagating his art theories and methods. By the 1940’s, Davis’ theory of elimination was already having a major impact on other artists of Davis’ generation. Artists like Willem de Kooning were already noticing Davis’ theories and reflecting it in their works. De Kooning’s black and white series is an important proof of Davis’ influences. Another artist influenced by Davis’ process of elimination is Frank Stella. His black and white paintings featured in Dorothy Miller’s groundbreaking MoMA exhibition Sixteen Americans (December 1959 – January 1960) reflect Davis’ influences. Yayoi Kusama’s exhibition of white paintings at the artist-run space Brata in 1959 all illuminated Davis’ theoretical influences inherent in works like Landscape (1932 / 1935), Untitled (Black and White Variation on “Pochade”) (c. 1956-1958.) or (Letter and His Ecol. (Black and White Version) (1962).

Born in 1892, Davis began his painting career around 1909 when he was still in his teens. He began his studies with the Ashcan artist Robert Henri. Throughout his career, Stuart Davis was constantly examining and reexamining his practice. He was continually evolving and searching for new ways of articulating his thoughts. Davis’ ever-evolving theories of “colorspace” pushed him towards the black and white compositions. He had an intense purpose engendered by his quest for objectivity in a way that gave credence to form and shapes of original drawings.

For Davis, something “known” must be central to the art-making process. The insertion of the “known” and Davis’ reliance on forms and shapes to create a link to the objective world was in stack contrast to the subjective nature of Abstract Expressionism. Although he understood that abstraction was the new realism uniquely suited to expressing modern life, Davis also knew that for a work of art to have meaning, it must include something that has relevance or is recognizable by the viewer. Davis’ theory of the inclusion of the “known” influenced some of his peers and some of the most important artists to follow including Donald Judd and Jasper Johns. Judd’s stacks or Jasper Johns’ flags, targets, and numbers are important examples of how Davis’ theory of the “known” influenced other artists.

Stuart Davis’ Search for a Universal Style

The search for a “Universal Style” dominated a large part of Davis’ career. His black and white compositions were a giant stride in actualizing that objective. Nevertheless, even as he pursued his quest for a universal style, he was also concerned about aesthetics. In his colorful paintings and black and white, archiving high aesthetics was paramount to Davis. His very colorful works magnetically captivate viewers because of their aesthetics. It is not surprising that one of Davis’ main objective as an artist throughout his life was increasing the popular understanding of aesthetics. That understanding reflected in the theoretical practices of a younger generation (later classified as Minimalists) as articulated in Frank Stella’s claim that “what you see is what you see.”

Lines Thicken brings attention not just to the uneasiness of an artist dedicated to always striving to interpret and reinterpret his ideas; it is also a centering of his importance in art history. Barbara Haskell was succinct in her description of Stuart Davis and his place in American history. In the catalog for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2016 Davis exhibition, In Full Swing, Haskell describes Stuart Davis thus: “Stuart Davis has been called one of the greatest painters of the twentieth century and the best American artist of his generation.”

Curated by Priscilla Vail Caldwell in collaboration with the artist’s estate, Lines Thicken: Stuart Davis in Black and White allows an opening for the examination of the artist’s creative career, and his search for new theories to actualize his thoughts. This is the Estate’s first solo exhibition with Paul Kasmin Gallery who is now its exclusive worldwide representative.

Paul Kasmin Gallery took over from the Salander O’Reilly gallery after many years managing the Davis’ Estate. It was discovered in 2007 that Lawrence B. Salander had secretly sold more than 90 among other works by Davis. In March 2010, Lawrence B. Salander admitted to selling those paintings and pleaded guilty to a $120 million fraud scheme. In addition to presenting Davis’ works in exhibitions to the public, Paul Kasmin Gallery will also publish a scrapbook. It will include archival materials that only very people have ever seen. Additionally, it will include family photographs and excerpts from the more than 10,000 pages of Davis’s studio journals on art theory.

When Davis died in 1964, he left behind a repertoire of works and theories. His creative advancements continue to influence a younger generation of artists. There is no doubt that he is one of the most important artists in American history. In addition to being one of the first artists to associate jazz and swing music with art, his influence on his contemporaries and those that followed stand him out. Although the focus of Lines Thicken is Davis’ black and white paintings, they are reminders of his beautify colorful paintings. In this black and white painting, we see colors reminiscent of works like Swing Landscape, 1938, The Paris Bit, 1959, and Report from Rockport, 1940.