ART NEWS

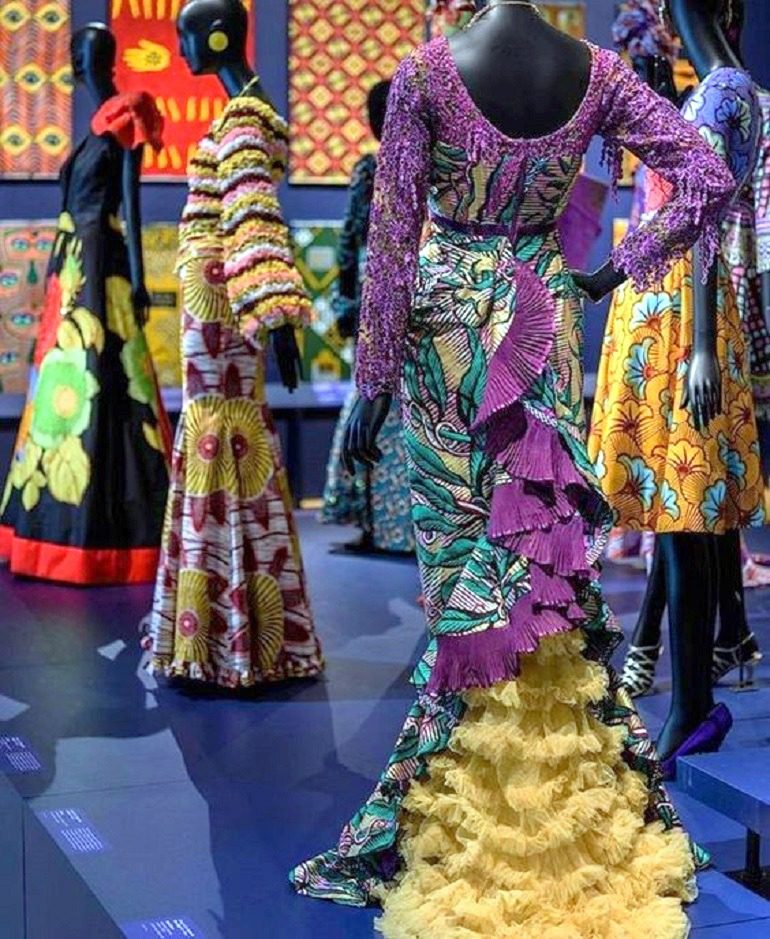

Beautiful dresses made from wax printed textile by Vlisco often described as authentic African fabric at the Philadelphia Museum of Art are part of African identity. Image: Vlisco

ART REVIEW: African Fashion on a Global Stage at the Philadelphia Museum of Art reveals the hidden history of the Ankara fabric and how Vlisco’s wax-printed textile with bold patterns became authentic African fabric.

BY KAZEEM ADELEKE

Details of beautiful dresses made from wax printed fabrics with bold patterns that are often described as authentic African fabric. Image: Vlisco

PHILADELPHIA – What is the true origin of the textile material Nigerians call Ankara? Why do people think it is manufactured in Nigeria or somewhere in Africa? These are the questions Vlisco: African Fashion on a Global Stage is trying to answer. The exhibition of designs made from wax-printed textiles at the Philadelphia Museum of Art tries to unravel a layered history of the African wax prints.

Ankara: A Layered History

Although the wax-printed textile is associated with Central and West Africa, the fabric has a layered and surprising history that transcends Africa and cuts cross across Europe. Until recently, when the production was moved to China and India, this beautiful material with bold and colorful designs was designed and manufactured in Europe.

The luxurious wax prints have their origins in the Netherlands. The story begins in 1846 with a company known as Vlisco. Soon after the company’s founding, it began exporting imitation batiks to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). Three decades later, the company found a new market in West Africa and took the opportunity to make its designs the center of attention. Before long, Vlisco materials became an integral part of the African culture. Soon, Africans began to claim it as their own.

African Identity On Wax Prints

Today, across Africa, African men and women wear wax print textiles with great dignity. The materials are made into beautiful African attire, handbags, and shoes. Additionally, they become curtains, pillowcases, and other luxurious items.

In many African countries, the fascination with wax printed fabric goes beyond luxury: its bold and colorful patterns are some of the reasons Africans assert it is authentically African. That sense of authenticity is why Africans embraced the fabric as their own. Nigeria is a great example.

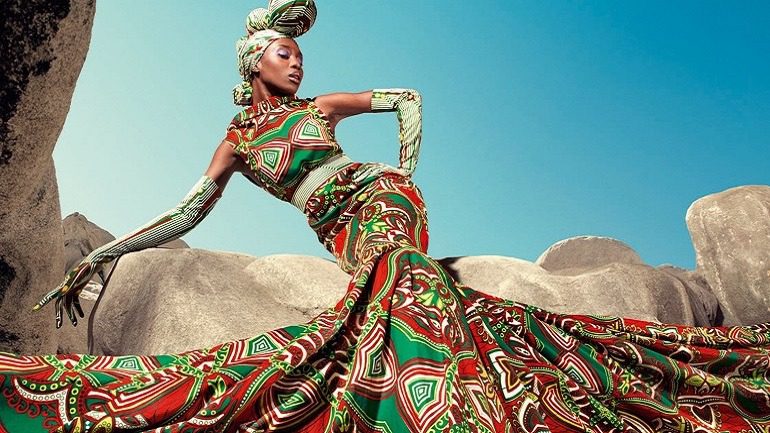

A beautiful woman showing off her dress made from wax printed fabrics with bold patterns. Image: Vlisco

In Nigeria, the beautiful textile with bold and colorful patterns is known as Ankara. If you ask a Nigerian woman where Ankara comes from, she will either say Nigeria or point to another African country. As wrong as the answer may be, it is understandable because Ankara is a major part of the Nigerian cultural identity. In pre-independence Nigeria, for example, Ankara served as an important medium for making political statements. Political organizations and groups wore Ankara to make political commentary and confront the oppressive British colonialists.

Soon after Nigeria gained independence in 1960, Ankara took on a different meaning: it became the fabric for making fashion statements. From Ankara, many Nigerian designers began creating incredible designs and African wear.

Borrowing from indigenous and Western designs, designers created some amazing designs. Soon, the importance of the fabric shifted from the need to express fashion sensibilities to an opportunity to express family unity and solidarity. During birthday parties, weddings, and other social events, it is not unusual to see families and friends dressed in Ankara as Aso Ebi.

Ankara as Aso Ebi

Aso Ebi (Family Clothe/textile) is a uniform dress that allows friends and family to show unity during festivals and ceremonies. While each member of a family or group has the freedom to design the fabric the way he or she wants, the common thread is the fabric’s bold and beautiful designs. The styles could include head wraps, iro and buba, gele, fila, skirts, maxi dresses, kufis, and many other designs.

The use of wax-printed fabric as an indicator of national identity extends beyond Nigeria. Known by other names in other African countries, this beautiful fabric has helped shape the concept of fashion across Africa. From Senegal to Mali, Cameroon, and Ethiopia, people continue to appropriate the fabric in different ways to enhance their geographical identity.

The association of African identity with the wax-printed textile has led to a relabeling. When the fabrics leave Vlisco, they are identified only by a stock number. In the African market space, however, they are renamed and assume new meanings.

In Idumota and other markets where these fabrics go on sale, the female traders who sell them have ways of identifying them. They give them names based on proverbs, current events, politics, religion, and material culture. Expectedly, a design may have multiple meanings and interpretations. The meaning and interpretation continue to morph with new meanings depending on usage and location.

Ankara Fabric: Relevance in African Societies

The naming and renaming of the wax-printed fabrics across Africa have enhanced their context of usage, giving them social meaning, status, and value. The cultural assimilation of the fabric with its beautiful prints continues to enhance its relevance in African societies. The majority of the designs on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art demonstrate how integral printed wax fabric is to the African experience.

One of the subtexts of the show is the celebration of dressmakers through an investigation of the textiles they use for their creations. On display are classic and new designs from the Vlisco collection and its in-house design team. Also on display is a selection of contemporary fashions by African and European designers using Ankara for their designs.

This is perhaps the most beautiful of Creative Africa, a series of exhibitions focusing on Africa at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Beautifully curated, the platform at the center of the room is the core of the show. It has mannequins wearing beautifully designed couture made from wax-patterned fabric. The runway-like display allows for a significant understanding of how designers are using the fabric.

Africa’s Celebrated Designers

Designs by famous African fashion designers are in this show. They include Pepita Djoffon, Leonie Amangoua, Josephine Memel, Ruhimbasa Nyenyezi Seraphine, Lanre da Silva Ajayi, and Philadelphia’s own Ikire Jones. The designs include wedding gowns, dinner dresses, gowns, and shirts.

This exhibition proves that the significance of the Ankara fabric as a signifier of African identity transcends Africa. In the United States, African Americans interested in associating with their African heritage are buying unique Ankara clothing. As expected, there are African fabrics on sale online and the focus is often on Ankara.

Many brick-and-mortar stores are also taking advantage of the increasing interest in African fabrics. There are numerous Ankara fashion stores in cities across the United States. There is Ankara fashion everywhere.

In Baltimore, many brick-and-mortar stores focus on women’s designs. On display are Ankara fashion designs for pregnant women, and wedding gowns, skirts, blouses, long dresses, and short gowns. The styles are limitless.

This exhibition explicates the complexities of identity. Dilys Blum, the museum’s senior curator of costume and textiles and the brain behind the Vlisco, was apt in saying: “You have to accept this idea that where something is made doesn’t limit its identity.”

Since identity is always in constant flux, it is not surprising that this beautiful fabric made in the Netherlands is African. Although the striking wax-coated cotton fabrics from which many of the designs on display have their origins in another country, Africans now see them as theirs.

Beautiful African Fabric Designs

Three beautiful women show off their dresses made from wax printed fabrics with bold patterns by Vlisco. Image: Vlisco

The lineup of wax-printed fabrics with bold patterns by Vlisco at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is part of African identity. Image: Vlisco

Beautiful dresses made from wax printed fabrics with bold patterns by Vlisco at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is part of African identity. Image: Vlisco